Margarita Simonyan

A well-known figure whose name is always listed amongst the top 20 most influential women in Russia, the editor-in-chief of both the Rossiya Segodnya news agency and RT TV network, Margarita Simonyan chooses her words carefully. As someone often called “the state speaker”, she needs to be extremely careful about answering any question, but especially one as important as “What does the Armenian Genocide mean to you?”

“One hundred years ago my great-grandmother’s family was killed. Her parents and elder siblings were slaughtered when she was about five years old. She only survived because the family members had enough time to wrap her in a carpet and lean it against the wall. The Turks simply did not notice her as she was standing there and witnessing the murder of her family.

My other great-grandmother told me how her brothers, sisters, and parents were all slaughtered in one night. Only she and her younger sister survived. Right before his death their father gave them a golden coin each that my great-grandmother hid in her mouth. She was lucky – a Turkish man from the area took her to his family. It wasn’t until several years later that she was able to leave them and go back home.”

The history of the family branch that started from this great-grandmother is described in Truth for My Grandchildren, a book by Margarita’s grandfather Sarkis Simonyan. It is Neneka’s story that opens the book.

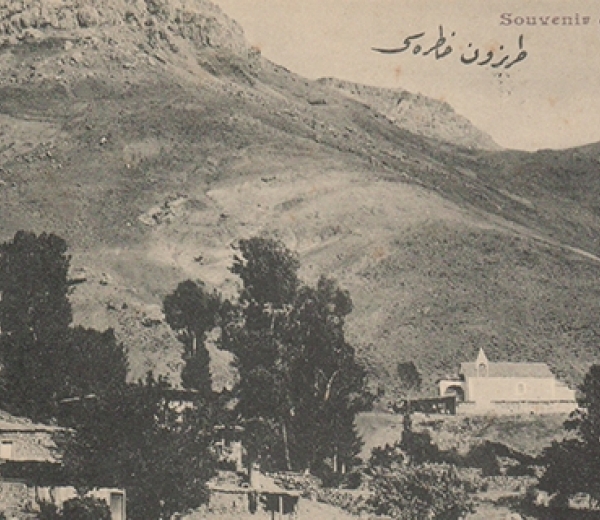

“She was still a little girl during the time of the Armenian Genocide in Trapezund (now Trabzon in Northern Turkey). Thanks to her beauty – she was blonde and blue-eyed – Neneka managed to escape yatagan. A rich Turk adopted her and did everything to give her a chance to learn Turkish and get to know the local traditions. He made her convert to Islam so she could eventually marry a Turk. In fact, the same thing happened to Ukrainian, Russian, Bulgarian, and Serbian girls everywhere within the reach of the Ottoman Empire.

As Neneka herself admitted, after many years spent living with a Turkish family, she forgot her mother tongue and became fluent in Turkish. It was only after Turkey was defeated in World War I, and with the help of the pressure from the foreign community, that Neneka was liberated and brought to Crimea. In 1922, at the age of 16, she married Nshan. This is how Margarita’s family settled in Russia.

“I remember Neneka – she looked after me until I was eight. As my granddad writes in his book, she would ‘give me yummy treats’ and tell me fairytales and stories. When the massacre occurred, she was about nine years old and had a younger sister, Alisa, who also survived. She was taken to Istanbul by a Turkish family. In his book, my granddad writes that they continued writing letters to each other until 1933, but then the connection was lost. Later attempts to find her – via the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Embassy, and the Red Cross – were all fruitless. The Turkish side never replied. We do not know what happened to Alisa. My younger sister was named after her.

You see, I am not an Armenian citizen, but a Russian citizen. It is hard for me to see the matter from a geopolitical point of view or speak on behalf of Armenia as a state. But at the same time, I am Armenian and so is my blood.

I can speak on behalf of the nation.

A nation normally doesn’t care about geopolitics or analyzing the country’s acquisitions and losses. That is why I’d rather talk about something else: as an Armenian who remembers her great-grandmother and all of her stories, it is inconceivable for me that some countries refuse to recognize the Armenian Genocide. It means that these countries reject the fact that my great-grandmothers and my family were treated in such a way. As any other human being, to me this seems unfair and detrimental for the world peace, however pompous that may sound.”

Margarita Simonyan does not see her convictions as stemming from her national identity. “Let me say once again: I am Armenian, but I am a Russian citizen. It is hard to say which of my values are Armenian, Russian, or universal. I’ve never thought about it. I also do not question how my nationality affects my actions. I adapted a more modern take on the matter.

I don’t see people based on their ethnic identity, and I don’t recommend that others do either.

It doesn’t matter, but the results of your work, your beliefs, your view of the world, and your professional qualities do. As for values, I studied in the States when I was younger, and I can tell you that the patriarchal “one-story” America shares ethics and traditions that are a lot more conservative than ours.

I will do all I can to raise my kids to be good people. First of all, I will try to teach them Armenian, which I myself regretfully don’t speak. Sometimes I find myself in situations where I feel uncomfortable because I cannot join a conversation in an Armenian-speaking environment and I don’t know what people are talking about. I hired a tutor who gives my daughter classes twice a week – they read books, tell fairytales, talk, and sing. My son is still too young, but as soon as he gets older, I will definitely teach him Armenian. A language you don’t learn as a child never becomes your first language.

I hope that Armenian will become my children’s first language.

Every year, on April 24, our family commemorates our ancestors who were murdered in 1915. Armenia was their homeland. This is the country that formed their culture, their values, and their personal traits. When I am working less than I am now, I would like to travel to Armenia to get a better understanding of it.”

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.