Sam Racoubian

The Racoubian family lived in the village of Gürün, not far from Sivas (Sebastia). The Racoubians were prosperous and quite well educated; they owned a pharmacy and a restaurant. Everything was relatively peaceful until 1914, when persecution of Armenians began in Sebastia following the Young Turk Revolution. It was then that many people began pondering emigration. The Racoubians also considered leaving, but didn’t have time to get away: at the end of 1914 Edward’s father Armenak was drafted into the army. Although he was notionally an officer, he was forced to carry out menial work. Armenak’s chances of survival were no greater than those of his wife Ovsanna and their five children. The Turks came for them in May 1915. Ovsanna, her four sons and only daughter barely had time to pack a few essentials when they were herded into the town square. From there, the “caravan of death” set out on its long march deep into the Syrian Desert. “In the beginning there were almost 10,000 of us, but in the end only 300 remained alive,” Edward Racoubian wrote in his memoirs many years later.

|

Edward’s father Armenak Racoubian |

|

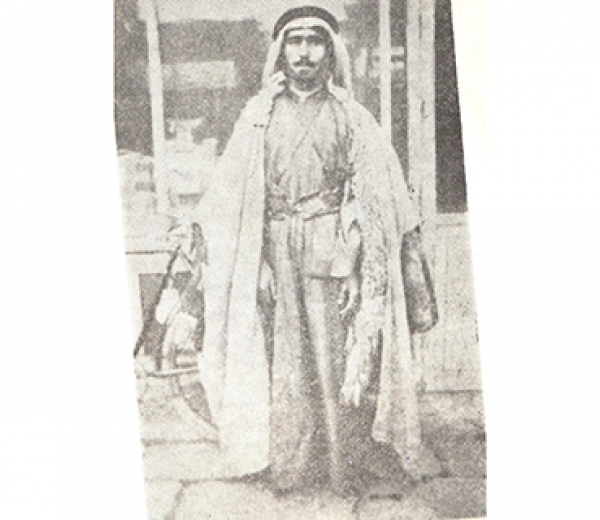

Edward Racoubian |

|

Edward Racoubian’s memoirs published as a book |

|

Edward Racoubian |

Edward Racoubian was more than 50 years old when he decided to once again visit the Syrian Desert where he last saw his mother. He found the Bedouin whom he served all those years ago. Although his one-time master often treated him very harshly, Edward thanked him for everything that he did. On the same trip Racoubian also found the gorge where he witnessed the slaughter of Armenians. The ravine was full of skulls and bones. Racoubian alerted historians who were studying the Genocide, informing them of the site of the mass grave.

|

Edward Racoubian with his family |

After all his struggles, Edward’s personal life was a happy one. He met his future wife Ripsime, also a refugee, in 1940. They got married and moved to Beirut. The happy couple had three children, all of whom received an excellent education. After graduating from the American University in Beirut, Sam Racoubian became a chemist and specialized in lab tests. Soon he established his own lab and later opened a private diagnostic center. Several clinics appeared after that, and now he has a whole chain of medical facilities.

|

Sam Racoubian with his family |

|

Ditak magazine |