Émile Lahoud

Submitted by global publisher on Thu, 12/17/2015 - 13:00

English

Intro:

The people of Lebanon have mixed feelings about the 11th president of their country, in office from 1998 to 2007. Some accuse General Émile Lahoud of being too pro-Syrian, others claim that his focus on defending his country came at the expense of the economy. But everyone agrees on one thing: it was mostly thanks to Lahoud that the bloody civil war in Lebanon came to an end in October of 1990.

Weight:

-3 200

Story elements:

Text:

The people of Lebanon have mixed feelings about the 11th president of their country, in office from 1998 to 2007. Some accuse General Émile Lahoud of being too pro-Syrian, others claim that his focus on defending his country came at the expense of the economy. But everyone agrees on one thing: it was mostly thanks to Lahoud that the bloody civil war in Lebanon came to an end in October of 1990.

Text:

The 79-year-old veteran of Lebanese politics never hid his Armenian roots and is proud of them to this day. Émile Lahoud’s mother, Adrene Karabajakian, was only five years old when her parents Hovhannes and Rebecca fled to Syria in an attempt to escape the Armenian Genocide.

Starting from scratch

Before April 1915 the Karabajakians lived in the town of Adabazar in the Ottoman Empire. Like most local Armenians, the former Lebanese president’s ancestors were craftsmen and traders. Hovhannes Karabajakian owned a tannery and a shop to sell his wares. The town’s Armenian quarter got word of the impending doom a month before the massacres. “The family council decided that Hovhannes and Rebecca, together with the little children, should leave town immediately,” says Lahoud. “Their relatives convinced them that little kids would slow them down, which is why they needed to set out immediately. The rest of the family was supposed to follow a few days later, but they were fated never to see each other again.”

Adrene was five at the time, her older sister — six. The youngest daughter, not quite a year old, died from starvation on the way. Rebecca was malnourished and her milk dried up. When the Karabajakians finally reached Aleppo, they heard news of the terrible events that unfolded right after their departure.

“Almost all of our relatives were slaughtered,” the former president says. “My grandmother counted almost 100 close and distant relatives who were killed. And that was our family alone. How many other families there must have been…”

Fortunately, in Aleppo Hovhannes Karabajakian was able to make use of his skills and experience working with leather. He built a new business from scratch. Soon the family moved to Damascus, where Hovhannes was tasked with overseeing leather deliveries for the Syrian army. The raw leather Hovhannes imported was used to make boots for soldiers and saddles for horses.

Image:

Text:

|

Jamil and Adrene Lahoud |

While working for the army Karabajakian was in regular contact with a young Syrian officer, Jamil Lahoud. The officer often stopped by his shop and sometimes came to the house. Soon it dawned upon Hovhannes that these visits had nothing to do with business, as Jamil did not hide his feelings for one of Karabajakian’s daughters. For several years the young man, who came from a Catholic Maronite family, wooed the beautiful Adrene and sought the blessing of her parents. The young couple wed in 1933.

A year later, they had their first son, Nasri. Years later, Nasri would become the Chairman of Lebanon’s Supreme Council of the Judiciary. Émile, who was destined to become the country’s president, was born two years later.

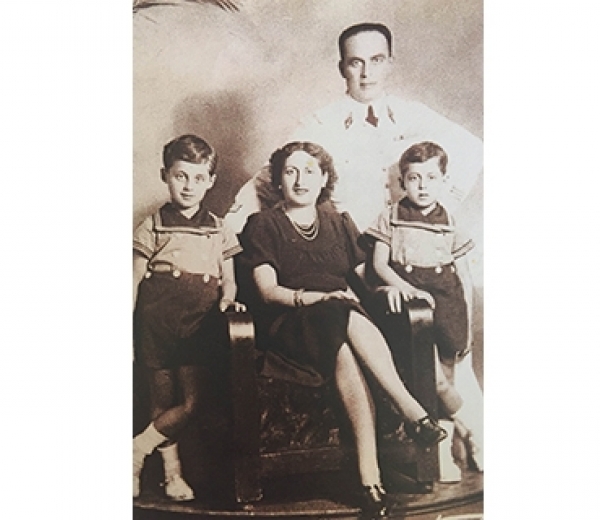

Image:

Text:

|

Jamile and Adrene Lahoud with their sons Nasri and Emile |

A family of politicians

Jamil’s military career took off. He was promoted to a higher rank and transferred to the Mount Lebanon governorate. Adrene’s parents moved to Beirut to be closer to their daughter. When Jamil was also transferred to Beirut, the family ended up living in the Karabajakians’ house, which Hovhannes had built across from the Armenian Orthodox church of St. Nichan.

“My father was a politician. He was a minister and so he had very little time for us. The same was true of my mother — she was always at her husband’s side for all sorts of society events and cocktail parties. Our upbringing was left in the hands of grandmother Rebecca,” Lahoud recalls. “She gave us everything she could, everything she had. We loved her madly.”

Image:

Text:

|

The Lahoud family with Rebecca (on the right) |

When Jamil and Adrene bought a new house, Émile remained with his grandmother. Rebecca Karabajakian suggested that the boy should go to the Armenian elementary school and his parents agreed. Even before school, Rebecca taught her grandchildren to write and read Armenian. Even today, the former president can still speak a bit of his mother’s native tongue. Unfortunately, he does not remember many of the letters. “I learned to read and write in Armenian before I learned any Arabic. Unfortunately, after grandmother died we heard no more Armenian and I began to forget many words. But when I met the president of Armenia and he spoke Armenian, I could understand a lot.”

Having received an excellent military education both in Europe and the United States, Émile Lahoud began his naval service. The handsome and stately captain drew the attention of many a young lady, but he chose an Armenian wife. “Émile’s mother was happy after learning that he decided to marry an Armenian. My parents were also very happy,” says the general’s wife, Andrée Amadouni. “Our wedding wasn’t traditional, but it was quite Armenian.”

Lebanon’s former first lady is also a daughter of refugees.

Her grandfather, Dr. Zare Amadouni, was an Armenian from Cilicia and a descendant of a noble princely family. In 1915 he escaped the massacre with assistance from the French, who helped the family move to Syria. His three brothers were killed.

Image:

Text:

|

Emile Lahoud |

General Lahoud and his wife have three children. Although they speak almost no Armenian, they have a great respect for their ethnic roots. “They are Armenians, just like my wife and myself,” says the former president. “Their mentality is Armenian, they are proud of their blood, especially our daughter Karine. She has lots of books on Armenian history. Our children dream of visiting Armenia. The sons of my brother are also Armenian patriots — one of my nephews even took up Armenian citizenship.”

Émile Lahoud has been to Armenia only once, in May of 2001. Despite a busy schedule of official events and working meetings in his two-day state visit, the Lebanese president found time to walk around Yerevan and to lay a wreath at the eternal flame in memory of the victims of the Genocide. This was a rare occasion when a statesman’s visit to Tsitsernakaberd was not a mere ceremonial event. “When I approached the eternal flame, I felt my eyes fill with tears,” Lahoud said. “I thought of grandmother Rebecca at this moment, her whole family killed. I recalled her words to me: ‘Never forget what happened to our ancestors. Otherwise it will turn out that all these people died in vain.’”

Even when he was still commander of the Lebanese Army, Émile Lahoud made a big effort to convince the country’s Parliament to condemn the crimes of the Young Turks. On April 3, 1997, the National Assembly of Lebanon proclaimed April 24 the “Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Genocide of Armenians.” Four years later, the Parliament officially recognized the Genocide. “The first Lebanese politician to raise the issue of recognizing the Genocide of Armenians was my father,” the former president explains. “Of course, I felt obligated to carry his initiative through. My political opponents tried to use this against me. They claimed that because I was half-Armenian, I was motivated by the Armenian community’s interests, not by Lebanon’s interests as a whole. But Lebanese society supported me. The people of Lebanon know that Armenians are justified in their demands.”

During Émile Lahoud’s nine-year rule, relations between Armenia and Lebanon attained a new level. Beirut began to actively support Yerevan on the international arena. The former president says that the Lebanese know the Armenians to be hardworking and conscientious people.

People remember that even after the Genocide, there were almost no Armenian beggars on the streets of Beirut.

“While others would beg with an outstretched hand, the Armenians would work tirelessly. Have no doubt about this: every Lebanese with at least a little bit of Armenian blood is proud of this fact. And I am one of them,” Lebanon’s 11th president concludes.

In honor of the peacemaking general, the inhabitants of Beirut named one of the city’s central avenues after him.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.

Subtitle:

Former President of Lebanon: “Armenians don’t beg”

Story number:

204

Author:

Artem Yerkanian

Header image: