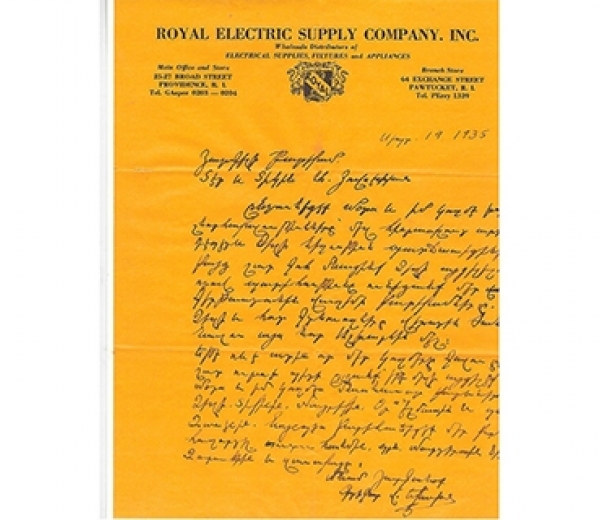

Michael Aram Wolohojian

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Michael Aram is best known to the world and to the Armenian community as a creative artist who took a simple idea – working with traditional Indian metal-crafting techniques, which he fell in love with as a youth – and transforming it into a global lifestyles brand with a distinct style that also draws from his Armenian roots. The grandchild of Armenian Genocide survivors from Arabgir and Kharpert (present-day Elazig in Turkey), today Michael Aram Wolohojian is a renowned designer. He launched his first metal-ware collection in 1989 after taking a trip to India, where he began working with local craftsmen. He currently sells his work in over 600 locations worldwide, having opened his first namesake boutique in Manhattan in 2007.

|

Pomegranate Sculpture, Natural Bronze, Oxidized Bronze, Powdercoat. The 25th Anniversary Atelier Collection. |

Michael Aram is active in the Armenian community in New York City, where he is a board member and a supporter of The Children of Armenia Fund (COAF), the Tumo Center for Creative Technologies and other organizations, as well as a supporter of the Eastern Diocese and his local Westchester church, St. Gregory the Enlightener, for which he created all of the interior metalwork and the steeple cross. He currently lives in New York City with his partner Aret, who is also Armenian, and two children, Thadeus and Anabel.

| Michael Aram in front of his flagship store in NYC. |

“My paternal grandparents were Genocide survivors, but they did not keep any records of their ordeal besides oral histories. They didn’t discuss their stories until much later in their lives. I was a teenager staying at their home one weekend with my brother and sister when we decided to make our grandparents pancakes for breakfast, a break from the sujukh (dried sausage) and eggs cooked in butter that was their usual fare. My grandfather said the pancakes were like the ‘khomor,’ the dough that they used to feed the camels on his farm in his village called Tadim, in the Elazig district of Turkey,” Michael recalls.

“I remember that we started fiercely asking questions because I had never heard them talk about what they referred to as the ‘old country,’ as though it were a thing of the past that one could never re-access physically or emotionally. My grandfather started telling us stories about his family, the separations, the murders, until my grandmother Mendouhi said, ‘Mugrdich, please stop!’ Right in front of us, they were arguing over the importance of transmitting the stories of their survival, and indeed, the survival of our family line.

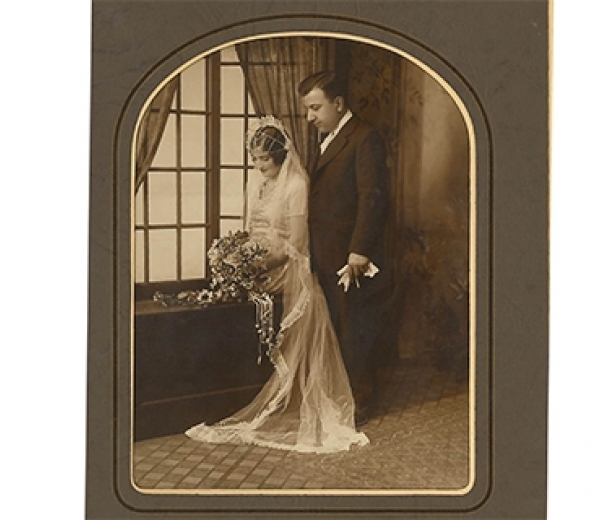

Mendouhi and Mugrdich Wolohojian

My grandmother spoke of the power that ‘Naci’ had to help them and others, and how his Turkish contacts had guided her mother and her two children to 'safe houses.'

She also told the story about her mother being arrested and imprisoned because she would not reveal the location of young Charlie. She miraculously escaped prison, either through her own wits or perhaps with the help of influence, contacts or money,” Michael says. “Needless to say, she spoke of how the three of them would not have survived without assistance from a few Turkish people who helped them along the way. It took her family seven years to arrive from Turkey to Marseille and, finally, America. She met my grandfather in Watertown, where he worked at the hood rubber factory until he saved up enough money to open up a ‘spa,’ or what we would call a ‘convenience store and soda shop’ in Arlington. He and Mendouhi had three children, Rose, Albert, and my father, John. So in a very real way, without the help of Naci, my great grandmother’s cunningness and some righteous neighbors, my family wouldn’t be here today.”

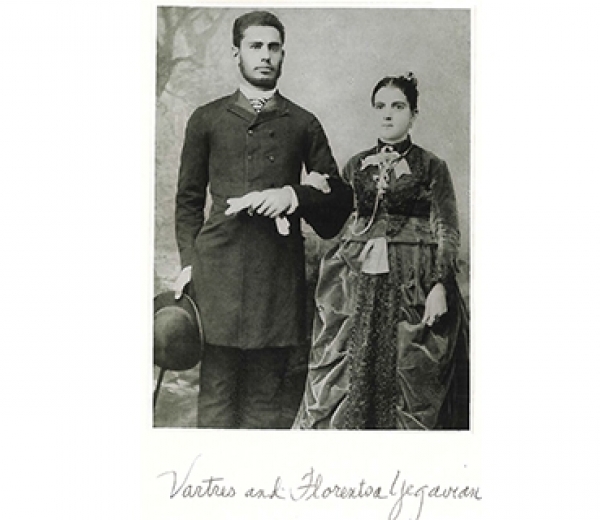

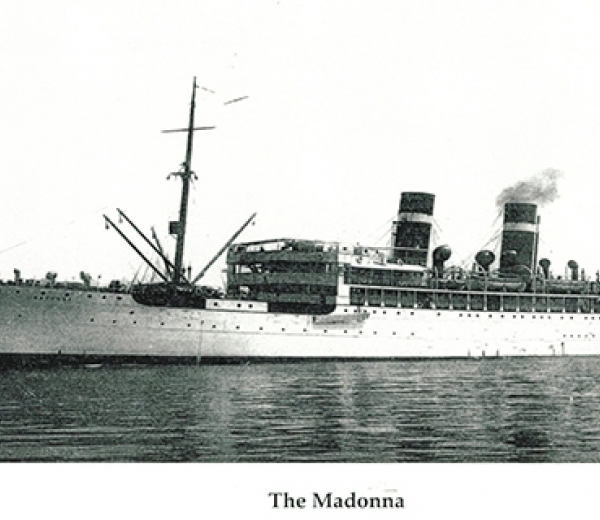

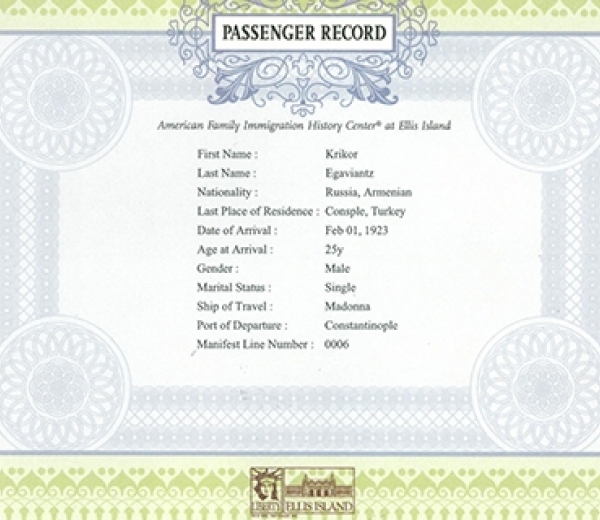

Michael Aram’s maternal grandfather was a descendent of Genocide survivors too. “My aunt Florence Wolohojian has kept impeccable family records. From her I learned that my great grandfather Vartres Yegavian (Egavian/Yegaviantz) was among the 200 plus Armenian intellectuals, poets, writers and prominent members of the Armenian community in Constantinople who were arrested and imprisoned on April 24th, 1915. He was never to return home or see his family again.”

|

Vartres and Florentsa Yegavian |

Vartres was from a family of wealthy businessmen and philanthropists. He had established his own business in Constantinople and had letterhead in four languages. He married Michael’s great grandmother, Florentza (Filaritza), in the mid 1890s. They had five children: Naomi (Noyemi), Michael’s grandfather George (Krikor), who, according to records, was born in Moscow in 1898, Anette, Edward and Larry.

|

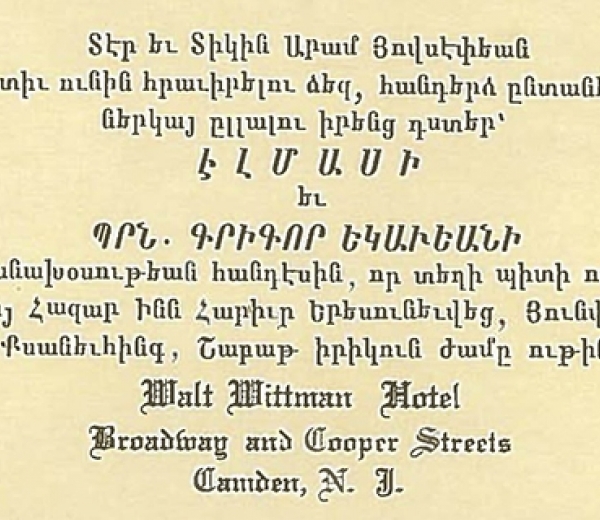

Aram and Zabel Hovsepian announce the engagement of their daughter Almas to George Egavian, 1936. |

“The family lived in the European part of Constantinople called Pera. Their circle of friends included the Russian consul and his wife, Anette. They were the godparents to my great aunt Anette. The consul's dress sword was presented to my great grandfather and was among the family's prized possessions, along with some objects, photographs, letters and documents that they carried with them to the United States later,” Michael explains.

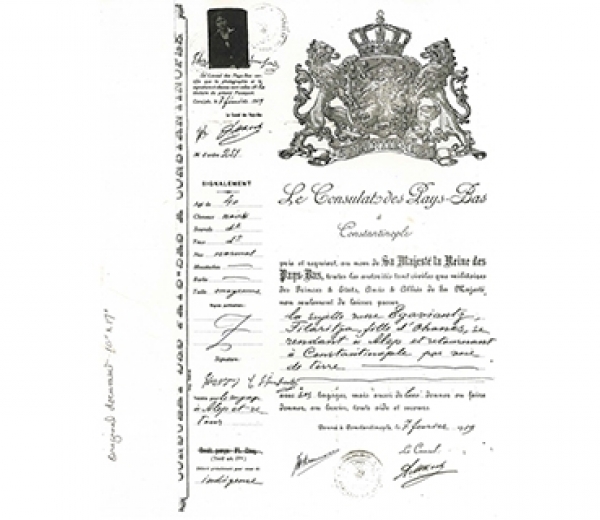

This certificate, accorded to those under protection of Her Majesty the Imperial Princess Eugenie Maximilianovna of Oldenburg, is issued by the Saint Petersburg Committee of the Sisters of the Red Cross to Vartres Egaviantz for the right to wear the rosette of the Red Cross in his boutonniere and to recognize his charitable activities in support of the Committee. January 20, 1907.

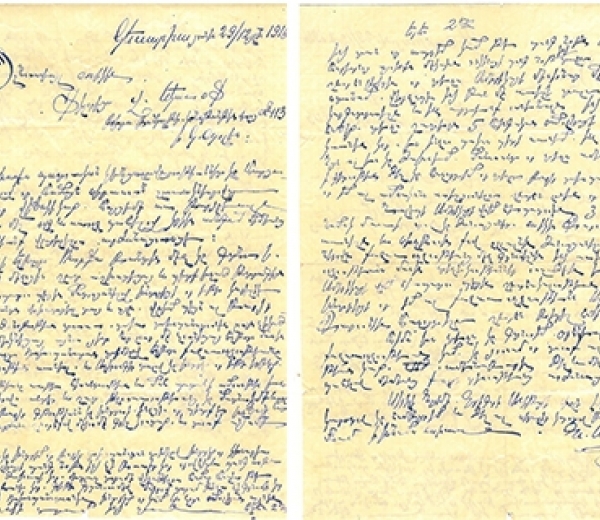

Despite his social position, like others Vartres would end up jailed in Urfa (now Sanliurfa in southern Turkey). In a letter to Filaritza in June 1916, Vartres’s brother Nazaret informed her that he was working with the American consulate in Aleppo to get Vartres moved to a prison in Aleppo.

When she returned to her native Aleppo, she and her mother Isgouhi Yeramian became active in a newly formed League of Nations project to rescue women and children survivors of the Armenian Genocide involuntarily held in Muslim households. A rescue house was established in 1921 in Aleppo and run by a Danish missionary, Karen Jeppe. The organization recorded personal histories of the women and children, the locations where they were forcibly removed from, what happened to them and how they survived. According to Jeppe’s report at Brussels University in September 1923, the commission succeeded in freeing about 2,000 Armenian women and children kept in slavery or in harems.

“My family is very traditional in many ways, and much like other families – except for the fact that we are an Armenian same sex couple. We are very involved in the Armenian community and had our son and daughter baptized at St. Vartan Armenian Cathedral. We also have a home in India, where I also have a workshop for my design work. It is perhaps at the workshop where I am most creatively satisfied and inspired,” Michael says. “I think my greatest achievement is creating a loving family and a business that supports many hundreds of other families around the world.”

By Christopher Atamian

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.