Vahe Berberian

|

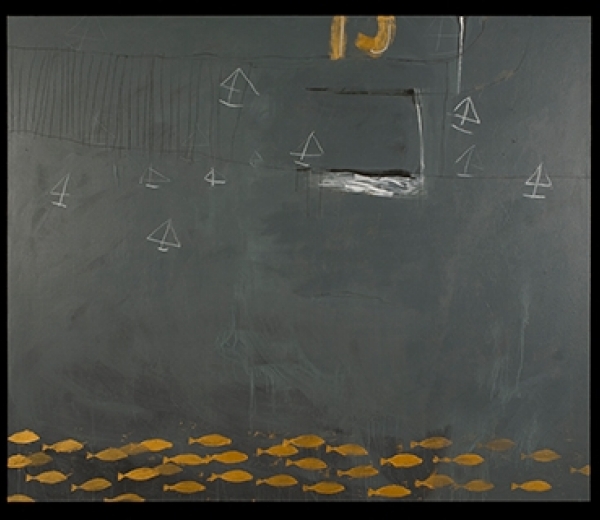

Antilias, 60 x 72, acrylic on canvas, 2008 |

His smiles are sincere and he peppers his conversations with “hokis,” an Armenian term of endearment, but his bountiful charm belies a morose family history.

Berberian’s father Raffi was one year old when he was sent on a death march through Deir ez-Zor in the Syrian desert with his mother, Vahe’s grandmother. The two first settled in Aleppo before moving to Beirut, where Vahe was born and raised. His mother’s entire family was massacred during the Genocide.

|

Vahe Berberian’s mother during a protest on April 24 |

Many families avoided recounting their horrific experiences to the new generation, but not in Berberian’s home. “In my case, it was the total opposite. They said: ‘This is exactly what happened, if you don’t remember it, you will be betraying us. For the longest time, I had a huge sense of guilt without having done anything to feel guilty.” One particularly disturbing story told by his grandmother was about how she tried to drown his father three times during the death march, but the Euphrates was so full of bodies, he wouldn’t die.

|

Vahe Berberian’s father with his students in Aleppo, Syria |

The feeling of safety was short-lived: he was soon diagnosed with bladder cancer, which led to numerous surgeries.

|

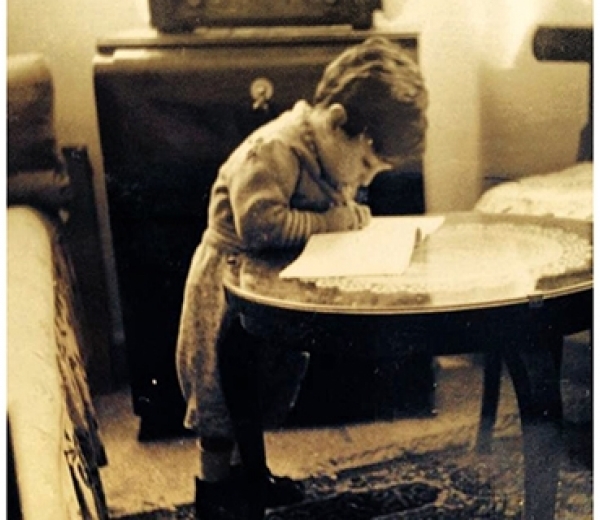

Vahe’s first attempts at writing |

Berberian didn’t have any illusions about how difficult it was going to be, saying, “We have 1.5 million people sitting on our shoulders and we’re trying to move forward and it’s so difficult.” But this tattooed 61-year-old regaling a crowd by mocking their - and his - own idiosyncrasies in Armenian was not concerned with limiting himself to a boxy paradigm. Five books, 13 plays, five comedy shows and hundreds of pieces of artwork later, his large following must appreciate that he wasn’t.

He unflinchingly embraces the role his culture has played in his work, saying it adds a whole new dimension to who he is: “My being Armenian has always been an asset, has always worked in my favor, without exception.” His culture is so much a part of him its role in his work seems a natural consequence of who he is, rather than a way for him to satisfy his audience or erase any residual guilt. And he uses it with great ease, showing that it can be inspirational without being overwhelming, that it can color perspective without being blinding.

Indeed, his irreverence to cultural norms by way of his appearance, jokes or art suggests an exceptional comfort with his Armenian identity, allowing him to achieve a sublime, enviable balance.

|

Vahe Berberian before a show in Paris |

We have come to the conclusion that in order to make an Armenian film, you don’t have to definitely make a film about the Genocide.

|

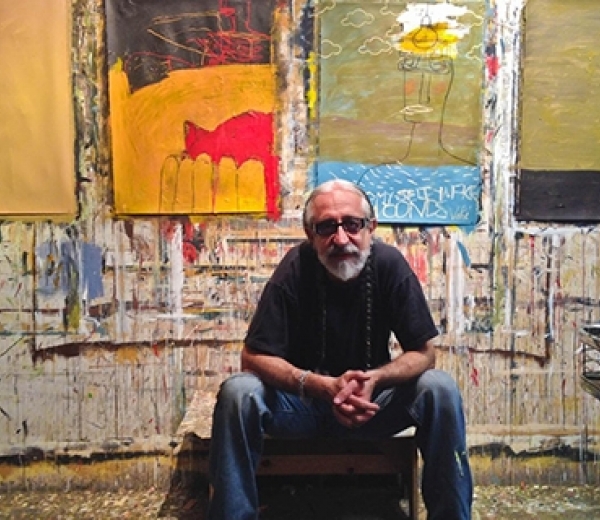

Vahe Berberian, photo by Armen Keleshian |

But to Vahe, there is no stopping. Berberian continues his one-man cultural revolution to uncover the beauty and art resting amid the vast Armenian landscape - and he’s dancing all through it.

By William Bairamian