Dickran Kouymjian

Submitted by Komrakova on Thu, 09/01/2016 - 16:31

English

Intro:

Former Director of the Armenian Studies Program at California State University, Fresno, Dickran Kouymjian is an Armenian-American university professor with encyclopedic intelligence, a mischievous look and the soul of a globetrotter. His biography resembles a labyrinth with no beginning or end, winding through Romania, the United States, Lebanon and France.

Weight:

-6 000

Story elements:

Text:

Former Director of the Armenian Studies Program at California State University, Fresno, Dickran Kouymjian is an Armenian-American university professor with encyclopedic intelligence, a mischievous look and the soul of a globetrotter. His biography resembles a labyrinth with no beginning or end, winding through Romania, the United States, Lebanon and France.

Text:

The immensity of his inner world becomes apparent by simply looking through the door of his museum-like house in the heart of Paris. There are countless objects of ancient art, but the jewels of this collection, among the watercolors and paintings by his friend William Saroyan, are a collage and a portrait by the great Sergei Paradjanov.

Son of survivors

The son of Genocide survivors, Dickran Kouymjian was born in Tulcea, Romania, where his parents from Chicago were visiting his paternal grandparents. His mother, Zabelle Kalousdian, was born in 1906 in Samsun, located on the Black Sea. Zabelle’s, father Dickran Kalousdian, was an instructor at the prestigious American College of Marzevan. Sensing the danger that loomed in the spring of 1915, Dickran entrusted his two youngest children, Arshavir and Zabelle, to his Greek neighbor, who kept them at his house. The children remained hidden until the end of the war. “This Greek neighbor was probably an associate of my grandfather Dickran, whose name I carry,” says Dickran.

Beside Arshavir, Zabelle had another brother and three sisters who died in 1915: the oldest (whose name is not known), Flora (18 years old), Nvart (17) and Jirayr (six). “They most probably embarked on an araba (cart) with their mother Hermone when the caravan left Samsun a few days after my mother and her brother found shelter at the Greek’s house. My mother and my uncle remember watching them moving away,” says Dickran.

His maternal grandfather faced an equally disastrous fate. After being arrested with other notables, he was killed outside Samsun. When the war ended in 1918, Zabelle and Arshavir were placed in an American orphanage at Kadiköy in Constantinople. Levon, the son of their father’s brother Kirkor, who had immigrated to the United States before the war, found the names of his little cousins on the list of orphans prepared by the American Near East Relief organization. He succeeded in bringing them to Chicago through New York.

Toros, Dickran’s father, was born in 1901 in Talas near Caesarea (now Kayseri) in Central Anatolia. He grew up in Smyrna (now Izmir), where he attended the Mekhitharist school. There, he began singing in the Armenian church of St. Stepanos. At the end of 1920, two years before Kemalist forces burned the city, he decided to leave for America. His grandmother provided the money to make the crossing by boat. Dickran’s paternal family managed to escape to Romania (after a stopover in Naples), where an ancient Armenian colony existed. Alone in Chicago, Toros continued his studies in the city’s conservatory of music, supporting himself with a scholarship granted to him by the American Lady Patrons auxiliary. Anxious to gain financial autonomy, he dedicated himself to the sale of oriental carpets and became cantor at the Armenian Church in the city. During an Armenian dance in Chicago, he met Zabelle.

The couple lost their first child, Janie, to pneumonia in 1933. Wanting to get away from the painful memories, they went to Romania when Zabelle was pregnant with Dickran. It was in Tulcea, Romania, that Dickran was born, as was his brother Armen two years later. The family remained in Romania because Toros wanted to live alongside his relatives. However, when war broke out in 1939, the U.S. Embassy in Bucharest asked its citizens to return home. In November, Kouymjian took the family back to America. Little Dickran was five years old; he spoke Romanian and Armenian fluently… far better than English.

An American childhood

Immersed in both Armenian and American cultures, Dickran was a curious adolescent and a brilliant student. He left home at the age of 18 to study chemistry and physics before changing direction and heading to engineering studies. Enrolled at the University of Wisconsin (Madison), he explored his interest in the cultural history of Europe. In January 1957, Dickran graduated and signed a six-month commitment as a reserve officer in the U.S. Army, stationed in Washington D.C. As a reserve officer he was sent to training camp in nearby Virginia, but lived off the base. There, young Dickran tasted the cultural and musical pleasures of the American capital.

In 1958 he went to Brussels, where the World’s Fair was being held, and wrote articles for the jazz magazine, Downbeat. Afterward, instead of returning to the United States, he extended his journey to Lebanon, where he found a part of the Kouyoumdjian family of Romania who had settled in Beirut. Along with a Canadian journalist, he covered the news of the Near and Middle East for the international agencies, the International Press Service (IPS) and Reuters. He hoped to interview the Dalai Lama, who had recently left his native Tibet (after its occupation by the Chinese army) to find refuge in Northern India near the border. Alternately, he went to Syria, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, and finally to India. When he arrived in New Delhi, he was dissuaded to go further. Nevertheless, Dickran risked everything and mentioned the name of Heinrich Harrer, the Austrian preceptor of the young Dalai Lama. This opening allowed him to interview the spiritual Tibetan in a huge wooden house in Dharamsala, overlooking the Himalayas.

A universal globetrotter

Dickran returned to Beirut and pursued his studies at the American University. In 1961 he defended his Master’s thesis on the conflict in the Armenian Church in the 1950s. He worked under the guidance of Father Karekine Sarkissian, who would later become Catholicos of Cilicia, then that of All Armenians in Etchmiadzin: a long-lasting friendship emerged. When he returned to the United States, he decided to pursue his Ph.D. at Columbia University, where a program in Armenian Studies was available. However, teaching and attending seminars was not enough for him. During this period, he lived in Greenwich Village and worked in the evenings at Harout’s, an Armenian restaurant owned by his architect friend Harutiun Derderian.

Along with his Ph.D. dissertation, defended in 1969 on Armenian numismatics and those of the neighboring regions from the 11th to the 13th centuries, Dickran created a literary agency named American Authors, Inc., whose office was located on Madison Avenue. During his time at Columbia, he met an Armenian native of Samsun. The two young men introduced their mothers to each other and his friend’s mother informed him that she had seen his grandmother being deported from Aleppo.

At Harout’s, where Oriental music and jazz concerts were held every night, Dickran met Angèle Kapoïan, a charming French teacher at the prestigious Chapin School for girls, attended by the offspring of the American elite. Their marriage took place in the early summer of 1967. “My marriage witness was the African-American lawyer, Bruce McMarion Wright, a friend of Senegalese President Leopold Sedar Senghor. He was the lawyer of jazz celebrities like Miles Davis and Art Blakey … a Harlem figure who was pressed to be a candidate for mayor of New York, who was also a great poet and a great lover of Paris,” Dickran recalls.

The young couple was getting ready to go to Cairo, where Dickran was to become an associate director of the Arab Studies Program at American University. He signed the contract a day before the outbreak of the Six-Day War, which prevented them from going directly to Egypt. Immediately after they got married at the Armenian Cathedral of Paris, they went to Yugoslavia and Turkey in a Volkswagen, while awaiting their visas to Egypt. In 1971, the couple settled down in Beirut, where Dickran taught Medieval Armenian history from 1958 to 1961. He also became the head of the Armenian Studies department at Haïgazian University. Among his students was the future Catholicos of Cilicia, Aram I.

In 1977, Dickran began a crucial phase of his academic career by becoming the Director of the Armenian Studies Program at California State University, Fresno. He remained in that position for 31 years.

Image:

Text:

|

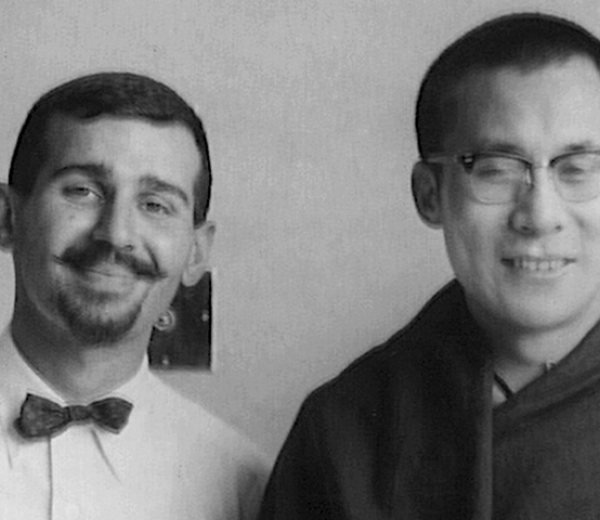

Dickran Kouymjian (right) with Sergey Paradjanov |

Extraordinary character

Dickran Kouymjian’s driving force throughout his international career is his unfailing passion for Armenian studies. This son of survivors, aware of the extreme fragility of the link that separates him from his family’s past, recorded his mother’s voice in the early 1980s as part of the collection of oral histories for the Armenian Assembly of America, which was funded by the United States government.

Passionate about literature and cinema, Dickran had a close friendship with William Saroyan, whom he accompanied during his last years as he too traveled back and forth from his home in Fresno to his apartment in Paris. Another meeting that marked Dickran’s life is the one with filmmaker Sergei Paradjanov in Soviet Armenia in 1987. During this period, Dickran taught Contemporary American Literature at the University of Yerevan. Paradjanov came to shoot a movie on the treasures of Etchmiadzin at the request of Catholicos Vazken I. However, the project failed, and Paradjanov insisted that Dickran return with him to Tbilisi, where he stayed in his house during a long Easter weekend.

Image:

Text:

|

A collection of stories released in tribute to Dickran Kouymjian on the occasion of his retirement from the University of Fresno in 2008 |

Later, Dickran travelled to Tbilisi again to study manuscripts. He met Paradjanov, who offered him a collage and wanted him to stay a while. He had already drawn a portrait of Dickran in Erevan. “He was a very generous man. It was unfortunately at Saint Louis Hospital in Paris that I last saw him just before his death,” Dickran recalls. “He painted my portrait in Etchmiadzin in a few minutes, with some ink and a handkerchief.”

At the age of 82, Dickran has not yet found the time to write down his memories. Others will take care of that. When he is not traveling, he can be spotted running at the Parc Montsouris, close to the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris, moving along the paths as he has moved through life – with purpose and grace.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.

Cover image: Dickran Kouymjian with the Dalaï Lama in 1958

Subtitle:

A man with 100 lives

Story number:

112

Author:

Tigrane Yégavian

Header image: