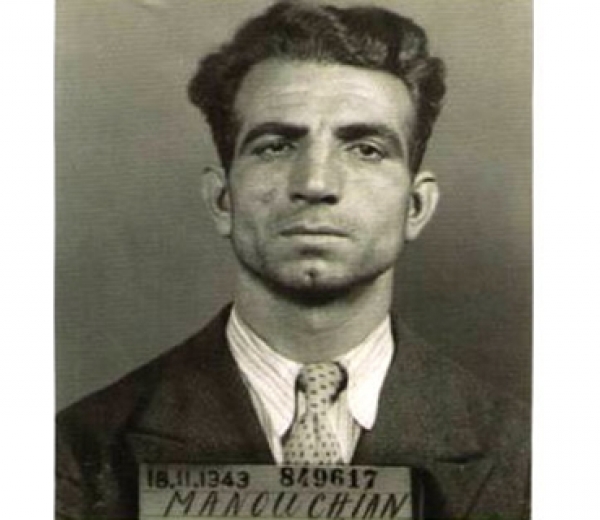

So central was my cousin’s role that the group is now also known as “Le Groupe Manouchian.” Streets and plazas are named after it, or after Manouchian himself, in Paris (in the 20th and 14th arrondissements), Issy-les-Moulineaux, Marseille and Yerevan. For their service to France and humanity, they were also immortalized in a poem by Louis Aragon called “Strophes pour se Souvenir,” set to music by Leo Ferre.

To say that I am proud that Missak is (even a distant) relative is a mild understatement. He made a difference in the world and he did not let the horrors of what he had experienced in 1915 stop him from moving forward and from brining the Armenian language and culture with him. As they say in Armenian, “Genadsset. To life!”

Bedros Atamian: fedayee, goldsmith, bootlegger

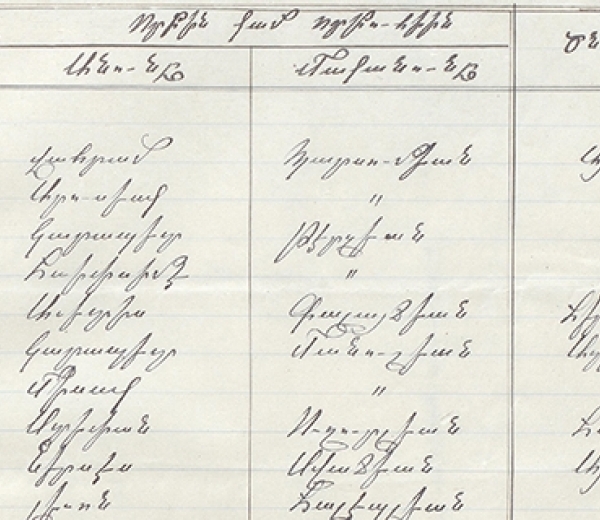

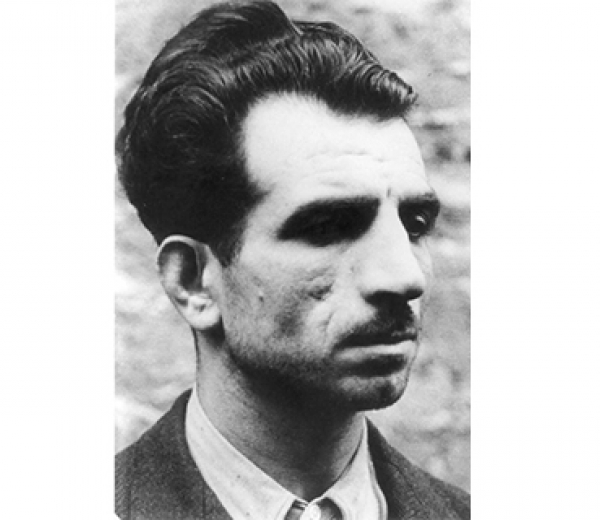

The other story I find fascinating is that of my paternal grandfather Bedros Atamian. Before becoming Atamian, our family name, it turns out, had been changed from Vosgeritchian to Kouyoumdji – the former means “goldsmith” in Armenian and the latter is a Turkish last name meaning “jeweler.” The changes were meant to help the family avoid persecution when the next roundups of Armenians began.

My grandfather Bedros was a peaceful man, a silversmith and businessman who became a fedayi, or freedom fighter, after seeing his family slaughtered by the Young Turkish gendarmes and the Kurdish Hamidiyes. He eventually fled from city to city, making silver cutlery sets for wealthy Turkish families. Although he spoke fluent Turkish as well as Armenian and Kurdish, many of these families must have known that this small man with a famously large nose was, in fact, Armenian.

On three different occasions the Turkish police tracked him down and tried to arrest him. On three different occasions he escaped.

He eventually made it to Zahleh in the Chouf Mountains in Lebanon. By that time he had made enough money along the way with his silver sets to establish a small “oghi,” or ouzo factory, in Zahleh. From there, he sent for a wife to be brought from an Aleppo orphanage filled with “the remnants of the sword,” Armenian women and children who had no family left. They married and had four beautiful children, all of whom led productive lives in Lebanon and then in the West: my father Georges, a journalist and manager of the Plaza and Saint Regis Hotel in New York; my uncle Dede, a successful banker in Beirut; my stunning red-haired Aunt Maro, who worked for Middle Eastern Airlines for many years, and my Aunt Reine, who was a homemaker and a prototypical Armenian mother. From them I have three cousins: Mikael, Raffi and Bedig.