Archi Galentz

Submitted by global publisher on Tue, 12/15/2015 - 12:04

English

Intro:

The works of Moscow-born artist, curator, writer and teacher Archi Galentz have appeared at over 70 international exhibitions and won multiple awards. A recurring theme in his art is the issue of Armenian identity and its evolution over time, from the collapse of the Soviet Union to the establishment of the independent Armenian republic. Galentz is a founding member of the “underconstruction” group, which brings together Armenian artists, and a member of the Art & Cultural Studies Laboratory.

Weight:

-3 100

Story elements:

Text:

The works of Moscow-born artist, curator, writer and teacher Archi Galentz have appeared at over 70 international exhibitions and won multiple awards. A recurring theme in his art is the issue of Armenian identity and its evolution over time, from the collapse of the Soviet Union to the establishment of the independent Armenian Republic. Galentz is a founding member of the “underconstruction” group, which brings together Armenian artists, and a member of the Art & Cultural Studies Laboratory.

Text:

For over 20 years now, Archi Galentz has been living and working in Berlin. The house, which he refurbished by himself, is more reminiscent of an art studio than a place of residence. The space is packed with Russian and Armenian books and decorated with posters of Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, while sculptures and paintings adorn every corner.

Archi Galentz was born in a family of artists. His father was a painter and his maternal grandfather, Nikolaj Nikogosyan, is a sculptor and a professor at the Stroganov Art School in Moscow. His paternal grandparents were also well-known painters in the Armenian Soviet Republic: in 1968, their house was officially turned into a museum. “Their paintings are still being made available to the public these days, though not as much as I would like,” says Archi, who still deeply loves his grandparents’ home, where he spent his early student years. “When I came to Germany, I planned to go back after graduation to turn my grandparents’ home into a private museum,” he recalls, his voice tinged with sadness and regret.

While he learned to restore paintings, display artifacts, illuminate showrooms and work with the press at the Berlin Academy of Arts, things in Armenia took an unforeseen turn. “The house had been turned into a museum without me and a director had been appointed. I was no longer needed,” says Archi.

Image:

Text:

|

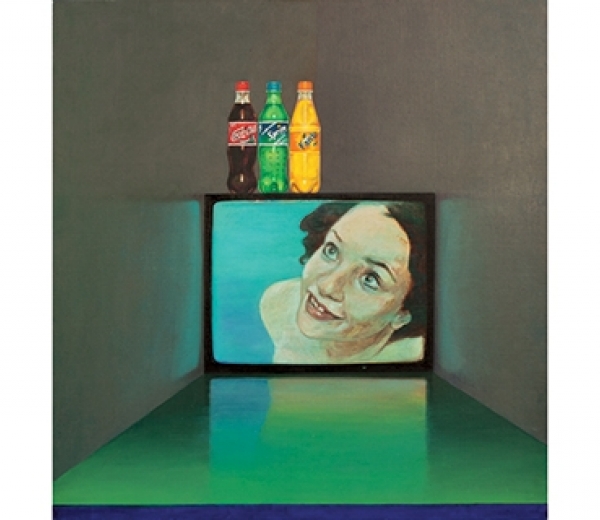

"The Choice" by Archi Galentz, 2002 |

Russia didn’t want him

In Soviet Moscow Archi Galentz went by his grandfather’s first name Harutyun and applied to design school. He spent two years preparing for the entrance exams. “I wanted to do something different, not necessarily painting. Design sounded modern and interesting to me,” he recalls. But access was denied to him. “I failed every exam, which was absolutely ridiculous,” he comments with hindsight. “For whatever reason, they did not want me there.” Six months later, in 1989, he applied to the National University of Arts and Theater in Yerevan and passed with flying colors. “I moved in with my grandmother Armine in Yerevan into the house my grandfather built all by himself. I still feel a closeness to them and their art,” says Archi. He recently showed one of his grandmother’s original artworks at an exhibition titled “GRANDCHILDREN – New Geographies of Belonging” in Istanbul.

Image:

Text:

|

A portrait painted by Archi’s grandmother Armine Baronian |

Armine Baronian was born in Adabazar in 1920. Even though World War I was over and massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire had subsided, by the age of four she lost her father and was forced to flee to Syria. Her mother was a teacher and her older brother Aram would eventually become a leading engineer in the field of drinking-water technology. Armine, however, fell in love with art during a visit to Italy in the late 1930s. “My grandfather’s fame had meanwhile spread across the Near East, making him one of the most highly regarded artists in Lebanon,” Archi says. “Armine went to Beirut to become his apprentice. She assisted him with his work for the world exhibition in New York. In 1940, she had her first exhibition in Aleppo, and four years later – another one in Beirut.

Harutyun was ten years Armine’s senior. He was born in Gürün in the Sivas province (present-day central Turkey) in 1910. He, too, was forced to leave his hometown early, at the age of five. His father was killed and the rest of the family was sent on a death march to the Syrian Desert. “According to information passed generation to generation, the family owned a weaving mill. My grandfather’s roots can be traced back to the ruling dynasty in the medieval Armenian capital city of Ani, but unfortunately there are no documents to prove it. He certainly had aristocratic habits,” Archi says.

Harutyun mother died shortly after arriving in Syria, emaciated by the march through the desert. “Together with his siblings, my grandfather was taken to an orphanage. This is where mentors discovered his love for art and started promoting his education.”

Harutyun grew up and travelled the Middle East, making a name for himself as a painter whose works adorn the Armenian church in Beirut to this very day. His big breakthrough, however, came with his participation in the 1939 New York World Exhibition.

“He is even said to have befriended late French President Charles de Gaulle when the latter organized French resistance against the fascists from his base in Lebanon,” Archi says. In 1946, Harutyun and Armine, by then – his wife, immigrated to Soviet Armenia.

“My grandfather would not talk much about what happened to him in 1915. But there is a drawing of his that deals with the horror, depicting a dead woman on the ground, embraced by her little kid. People who experience such atrocities often express their anger through art. Harutyun’s paintings are unexpectedly colorful and bright. My grandmother’s art is also characterized by its humanitarian appeal and sublimity. Even though Soviet art critics saw my grandparents primarily as victims of Genocide, they were more than that. They lived an active life, singing praise to it,” Archi says emphatically.

Image:

Text:

|

Archi Galentz and his bride Armine Torosyan at their wedding stand against the backdrop of a photo of Archi’s grandparents Harutyun Galentz and Armine Baronian |

Driven by thirst for knowledge

Archi was in Armenia when it gained independence of Armenia and witnessed Nagorno-Karabakh’s attempts to achieve self-determination. “My early student years definitely shaped my world view. It was a time of radical change and political upheaval. The conviction that society is capable of transforming and making a difference inspired me back in those days and has inspired me ever since,” he says.

Image:

Text:

|

Archi Galentz, "Banner," 2015 |

After a three-year stay in Yerevan he realized that he still lacked answers. “I developed a serious interest in art. I wanted to know what art was. That question I was asking would not be answered by anyone, not by my family and not by my professors at university,” he remembers. In the 1990s he came to Germany as an exchange student, looking for answers. He applied to study visual communication, industrial design and liberal arts at the Berlin Academy of Arts. He was accepted. “I spent many hours in the library, delving into art history,” he recalls. After graduation he held numerous solo exhibitions and taught art, writing many articles on the subject. In 2008 he opened his own studio named “Interiordasein,” which welcomes both artists and art lovers. Today, its showrooms boast a fine collection of contemporary Armenian art.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.

Subtitle:

Third-generation Armenian artist living and working in Germany

Story number:

205

Author:

Irina Lamp

Header image: