Dikran Altun

Submitted by global publisher on Mon, 02/01/2016 - 12:45

English

Intro:

After Armenia regained independence in 1991, the new state had no diplomatic relations and no political or economic ties with Turkey. The only direct connection between the two countries was by air. The man behind that route was Dikran Altun, a Turkish Armenian businessman. For Altun, who was born in Erzurum, lived in Istanbul and studied at the finest institutions of the Armenian diaspora, it hasn’t always been easy to identify with his heritage. Yet Armenia has always been his source of inspiration.

Weight:

-4 500

Story elements:

Text:

After Armenia regained independence in 1991, the new state had no diplomatic relations and no political or economic ties with Turkey. The only direct connection between the two countries was by air. The man behind that route was Dikran Altun, a Turkish Armenian businessman. For Altun, who was born in Erzurum, lived in Istanbul and studied at the finest institutions of the Armenian diaspora, it hasn’t always been easy to identify with his heritage. Yet Armenia has always been his source of inspiration.

Text:

“I feel like a cell phone that must be charged every night. If I don’t visit Armenia once a month, I don’t get recharged and cannot live here in Istanbul,” Dikran says.

The long road to Turkey

Altun’s family hails from central Anatolia. His father’s side is from the Yozgat village of Burunkshla (Burunkişla) and his mother’s – from the village of Tomarza in the Kayseri/Gesaria region. Until 1915 Burunkshla’s entire population was Armenian. It had two churches and a school. “In 1915 my grandmother Srpouhie had two children and was married to her first husband. She lost him in the massacres. Leaving their two children at an American orphanage, she went to Kayseri, where she met and later married my grandfather Dikran Altun,” Dikran junior explains. The couple had two sons and two daughters in Kayseri – including Nazar, Dikran Altun’s father.

The elder Dikran Altun originally bore the last name Altunian, but it was changed in 1934 when Turkey passed its “surname law,” requiring all citizens to adopt a hereditary, fixed family name. The legislation also required everyone to take on a Turkish language name.

“When my grandfather went to register his last name, he said ‘Altunian.’ The official said that Altun would be sufficient, and that’s what he wrote in the log,” Dikran remembers.

Dikran’s grandfather, a mason, died at a young age. Altun’s father Nazar, then just 12 years old, relocated to Istanbul with his family. “My father was only able to attend school up till the second grade in Kayseri. When the family – his mother, two sisters and a brother – moved to Istanbul, he had to start taking care of them.”

Dikran Altun’s mother Vartouhie was born in the Kayseri village of Tomarza. Her father, Nigoghos Barutian, fell victim to the Genocide. In 1915, before the massacres began, his father and uncle left for America. Soon after, Nigoghos, his mother and two sisters were exiled to Deir ez-Zor along with thousands of other Armenians. First they had to walk and were then herded onto a train.

Dikran describes his grandfather’s journey as if it happened yesterday: “Every morning, the train would stop. The dead were removed, the wagons washed and cleaned. One day, in the stony desert, everyone got off the train so that it could be cleaned. He was just a child and started to play with the stones. He turned around and saw that the train had gone. Most likely, his mother deliberately left him there because one sister had already died on the train.”

Master lives in the desert

An Arab found Nigoghos in the desert and took him to work in his home. Later on, foreign soldiers came to round up all Armenian children in the village. The Arab denied that he was taking care of Nigoghos. But the boy overheard the soldiers – who were probably members of the Armenian Legion of the French army – speaking Armenian among themselves. The soldiers took Nigoghos to an orphanage in Aleppo. Months later, in the orphanage, Nigoghos met a horse rider who said he was going to Tomarza. Nigoghos joined the horseman and first resettled in Hadjin (present-day Saimbeyli). He later made it all the way back to Tomarza. When he arrived, he was taken in by one of the Armenian families that had stayed and later married one of their daughters. “They would ask, ‘where did you learn Arabic?’ He would answer: ‘I learned it from my master.’ Who was his master? He didn’t remember. Where did he live? ‘The desert.’”

A matter of principle

When Dikran Altun’s father moved to Istanbul, he began working as a dental assistant. In time, he set up his own dental practice. Years later, in search of better work, he moved to Erzurum with his wife Vartouhie. That’s where the couple’s middle child, Dikran, was born.

Image:

Text:

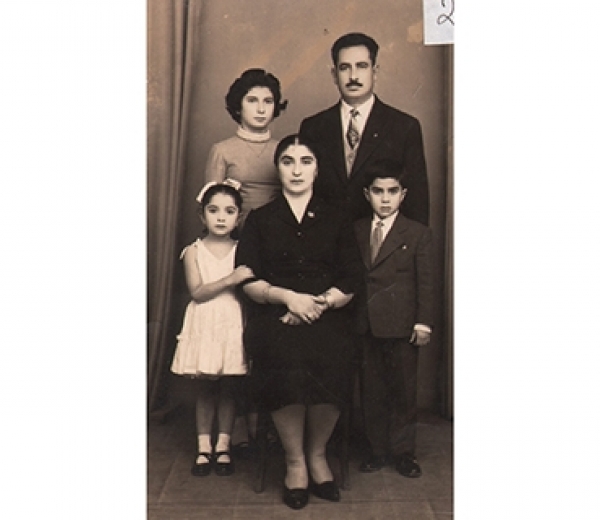

| Dikran Altun with his parents and sisters |

Nazar Altun only had three years of schooling and couldn’t read or write Armenian. But he made it a matter of principle that his children learn his mother tongue. Thus, when Dikran was five, the family moved back to Istanbul because there was no surviving Armenian community to support a school in Erzurum.

Dikran first attended the Sahagian School in Samatya, later transferring to the Hintlian School in Şişli. “I don’t know where my father heard that there was a school called Melkonian in Cyprus where they taught Armenian. Anyway, he sent me there and I stayed for six years,” Dikran says.

Studying in Cyprus was more than just an education for the young man: “Melkonian not only gave me a diploma, but also a wife! It was there that I fell in love with my wife Shnorig, whom I later married.” Graduating from Melkonian at the age of 18, Dikran Altun left for Beirut and studied economics at Haigazian College and the American University of Beirut.

After graduating Dikran returned to Istanbul and began to work with his father, who, having long left dentistry, was now in the construction business. Dikran continued the family business by himself for a time before getting involved in the aviation industry, mostly in Turkey and for a while in the United States.

Image:

Text:

| Dikran Altun with his wife and children |

Two men change course of history

Dikran’s first contact with Armenia dates back to his student days in Beirut. He first visited the country of his ancestors in 1972. Many years passed, but when Altun was back in Istanbul and Armenia was on the brink of regaining independence, two Armenians from Yerevan visited his shop. “I was interested in hearing more from people from Armenia so I invited them for dinner,” Dikran says. “One of the guys was named Ashot and the other – Telman. I never understood who they were. They told me I had to visit Armenia. I went two months later.” Later it turned out that Ashot was Ashot Safaryan, Armenia’s minster of industry, and Telman Ter-Petrosyan was a member of parliament. Altun saw a country struggling to rebuild after the 1988 earthquake and grappling with the challenges of its new independence. He decided to help. Since then, he’s visited almost every month, bringing different projects with him.

On one of those trips he decided to search for a family tie that was lost 100 years ago. He learned that one of the children from his grandmother Srpouhie’s first marriage was living in Armenia and set out with some friends to find him. They found the man’s house in Ijevan but sadly, Altun’s uncle Aram Torosian had passed away the previous year. “That boy was two when my grandmother left him. But at least I was lucky enough to make friends with his children,” Dikran says.

The closed border between Armenian and Turkey was a source of deep frustration, so Dikran got busy with the difficult work of opening it up on his terms.

Thanks to his delicate negotiations with Armenian and Turkish authorities, regular direct flights between Yerevan and Istanbul were established in the 1990s.

“If I hadn’t started that work back then, perhaps there still wouldn’t be any air link between Turkey and Armenia today. It’s the only link, the only open border,” Altun says proudly. “It was a profitable venture at first, but has been operating at a loss for the past three or four years. I thought about shutting it down, but didn’t know who would continue it. I didn’t want to be responsible for breaking the only link. I needed to find someone as crazy as I to want to continue, and it was good that I found the right kind of lunatic and transferred the business to him.” To this day, that Yerevan-Istanbul flight remains “the only open gate” between the two countries.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.

Subtitle:

Turkish businessman and mastermind of the only open gate between Armenia and Turkey

Story number:

193

Author:

Sargis Khandanyan

Header image: