Shant Mardirossian

Submitted by global publisher on Mon, 02/08/2016 - 23:16

English

Intro:

Near East Foundation (NEF) Board Chairman Emeritus Shant Mardirossian was born in Beirut, Lebanon. In 1969 he moved to Woodside, Queens with his family. He recalls briefing his fourth grade class on the Lebanese Civil War in their weekly current events discussions: that’s when he realized he had a passion for history and Middle Eastern affairs.

Weight:

-4 700

Story elements:

Text:

Near East Foundation (NEF) Board Chairman Emeritus Shant Mardirossian was born in Beirut, Lebanon. In 1969 he moved to Woodside, Queens with his family. He recalls briefing his fourth grade class on the Lebanese Civil War in their weekly current events discussions: that’s when he realized he had a passion for history and Middle Eastern affairs.

Text:

Mardirossian went on to earn his B.A. and M.B.A. from the Lubin School of Business at Pace University and pursued a successful career in finance, currently working as a partner and chief operating officer at Kohlberg & Company, a middle-market private equity firm.

Chance of a lifetime

While Shant was growing up, his grandparents — all of whom had survived the Armenian Genocide — didn’t discuss the details of what had happened to them in 1915, though he knew they had endured terrible hardships.

Some of Shant’s family members had been saved partly thanks to efforts organized by Near East Relief (NER), an American institution now known as the Near East Foundation.

When he was asked to join the NEF Board, his desire to learn about his family’s past and to help others who had suffered similar challenges led him to gladly accept the offer.

One day, the late banker and fellow NEF Board member Antranig Sarkissian showed him boxes filled with photographs of Armenian orphanages established by NER that were being kept in warehouses. Recognizing the historical significance of these archives, Mardirossian and Sarkissian convinced the NEF that these documents should be professionally archived, and in 2003 the NEF organized its first exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, curated by Neery Melkonian. At the time, the NEF worked mainly in countries such as Morocco, Mali, Egypt, Jordan, Sudan and Palestine. In 2004, Mardirossian suggested that they “return to Armenia.”

Under his leadership, the NEF started a small pilot project in Armenia to aid economic development in rural villages, later expanding to train female victims of domestic violence to start small business. The NEF continues to be an innovator in the region thanks to its “Olive Oil Without Borders” program, a peace-building initiative between Israeli and Palestinian olive farmers. The NEF also responded to the Syrian and Iraqi refugee crises by assisting and teaching refugees to establish small businesses in their host communities of Lebanon and Jordan.

Image:

Text:

|

Shant Mardirossian’s grandmother Mary Libarian |

An American orphanage saves lives

Shant’s paternal grandmother Mary Libarian was only eight years old when she made the trek from Aintab (today’s Gaziantep, southern Turkey) to Aleppo, Syria, deported along with other members of her family. Libarian’s parents died of disease and starvation during the long march to Syria and she was left an orphan along with six siblings. Two of her brothers escaped the convoy and tried to get back to their home village — one of them returned, but another disappeared, was killed or assimilated. To this day, no one knows his fate. “It’s a mystery,” Shant notes, “that almost every Western Armenian family has.”

The other siblings traveled from village to town, from Aleppo to Kilis, sometimes finding refuge along the way and sometimes forced to beg for food. They ate grass and became sick, slept outdoors in church courtyards and watched fellow Armenians die all around them.

Mary and her siblings spent time in American Protestant orphanages, including one in Kilis. These orphanages were eventually brought together under the umbrella of Near East Relief. At one point after World War I, Mary tried to get back home, but ongoing conflict and the arrival of the Nationalist Kemalist army prevented her from going. So she continued on to Urfa (modern-day Sanliurfa, southern Turkey), where she met Mardirossian’s grandfather. Along with other survivors, they made it to Aleppo.

Image:

Text:

|

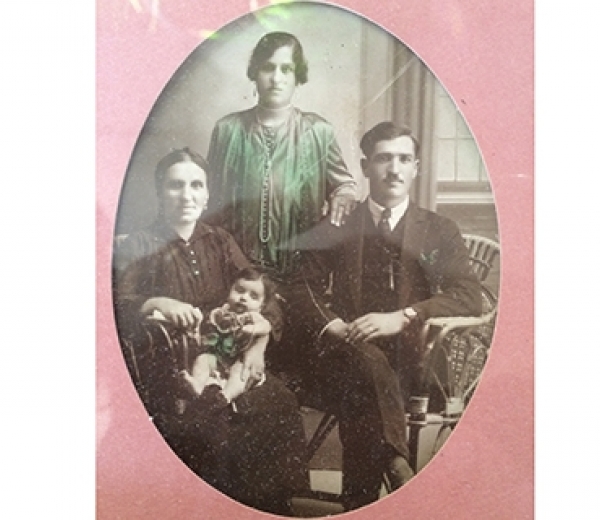

Mary Libarian Mardirossian (center), Garabed Mardirossian (right), Mrs. Lucararian (left; family friend) holding Vahan Mardirossian (Shant’s uncle)

|

After his grandmother passed away, Shant read the memoirs she left behind for her children under the simple title “My Mother’s Notebook.” The memoirs make for some heartbreaking reading:

“We were driven out of our homes. We got on the road… During the same year I lost my mother and father…After they were gone the suffering got worse…We were under the tents in a dessert called Shatma when the news came that we were going to be driven to Der Zor…My older brother Hovhannes managed to help us escape from the camp to a city called Kilis. My brother could not stay there for long hence they managed to take off to other cities in Turkey. One of them went to Etesia (the old Armenian name for Urfa) and the other to Aintab (we never heard from my brother Yesayi again) … It was our neighbors that helped us to get into the orphanage. There were five of us (four sisters and the youngest of the brothers, Hagop, 3-4 years old), the oldest was my sister Takouhi, who was only 15 and was taking care all of us the best she could. My youngest sister was very young. She had just stopped getting mother’s milk a few months before my mother died.”

While some orphanages were modern and well supplied, many were bare bones. Another passage from “My Mother’s Notebook” illustrates the difficult conditions that the brave souls running these orphanages toiled under:

“At the orphanage, we were always protected by any means that they were capable of from any intruders. But sometimes by the order of the Kaymakam (the town administrator) soldiers came and ordered us to line up, and they picked anyone that they wanted to take away…To escape this situation, the den mothers cut our hair short and dressed us like boys. Den mothers hid the older girls in the basement’s crawl area for hours, so they wouldn’t be picked up by the solders. Fifteen-year-old girls like my sister Takouhi had suffocating experiences from existing heat in that crawl area.”

Despite the grief she endured, in her book Mary also thanks some local Muslim families that helped the siblings along the way:

“We came to a village; we were welcomed by the locals, they gave us big houses with courtyards in the middle. They did not take us to the city because they said we were dirty and full of microbes. But our food was delivered from the city, at least thanks for that. And there were some neighboring mothers who were taking care of us also.”

Image:

Text:

|

Mary Libarian, Queens, New York, circa 1990 |

A generation saved

Shant Mardirossian is proud to have been serving as director of the Near East Foundation for the past 13 years and as its chairman for nine: “You have to understand the scope of NER’s activities. They saved over 130,000 orphans…the organization was launched specifically in response to the 1915 Genocide as a large-scale relief operation, soliciting donations from the American public to alleviate the suffering of the Armenian people,” he says.

As the first broad national appeal of its kind, the NEF’s use of mass media outlets was unprecedented. It also enlisted the support of celebrity spokespeople such as child-star actor Jackie Coogan, Ambassador Henry Morgenthau and citizen volunteers.

The results were extraordinary: between 1915 and 1930, NEF raised $117 million (equivalent to over $2 billion today).

A thousand men and women served overseas and thousands more volunteered throughout the United States. NEF built hundreds of orphanages, vocational schools and food distribution centers, and saved the lives of over one million refugees. In 2015, U.S. President Barack Obama mentioned the NEF in his annual April 24 address as “a pioneer in the field of international humanitarian relief.”

As a follow-up to the travelling exhibit “They Shall Not Perish,” Mardirossian recently commissioned and produced a documentary, written and directed by George Billard and slated for release in 2016. As another way of thanking peoples of the Middle East who helped Armenians survive 100 years ago, NEF and 100 LIVES recently announced an eight-year long educational scholarship program that will benefit 100 at-risk children from the Arab Middle East. 100 LIVES co-founder and philanthropist Ruben Vardanyan’s grandfather was also rescued by the Near East Relief.

Image:

Text:

|

NEF Board members and friends at the Kazachi Post in Gyumri, Armenia, in front of an old NEF orphanage |

Life has a circuitous way of bringing one back to one’s origins, and that is certainly true for Shant – a man with a cause that continues to give back to the people it was meant to serve. It’s not surprising that Mardirossian gets emotional when reflecting on this irony:

“Who would have thought that the grandson of one of the orphans that was rescued by the Near East Foundation would one day become its chairman and lead the organization through its centenary? It just goes to show that saving even one life has a ripple effect on the generations that follow,” he says.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.

Subtitle:

Chairman emeritus of Near East Foundation

Story number:

225

Author:

Christopher Atamian

Header image: