|

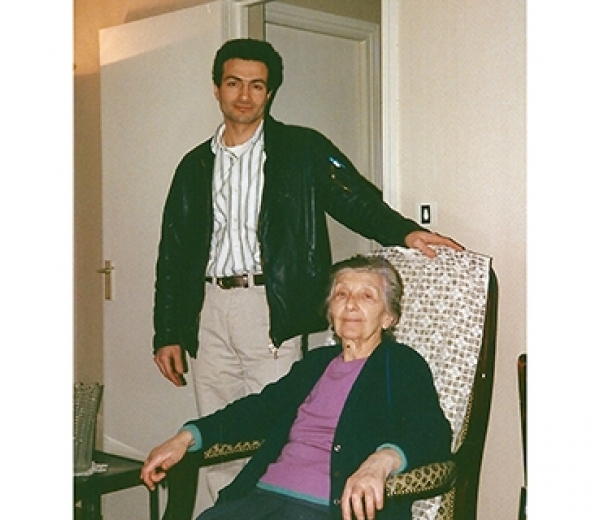

Little Agavni (first row, center) in her maternal grandmother’s arms. Afyonkarahisar, 1911

|

A childhood of flight and loss

Agavni Kalfayan, nee Papazian, was born in 1910 in the city of Afyonkarahisar, located in the center of western Anatolia between Izmir and Ankara. Her merchant parents, Hakop and Takui, were members of the city’s bourgeoisie. They had five children, one of whom was adopted.

In the spring of 1915 Agavni’s parents felt the imminent danger and decided to entrust their youngest child to a maternal aunt, also named Agavni. The aunt and the niece were supposed to go to Smyrna (now Izmir) to stay with Agavni’s maternal grandmother Maria Muradian, but when they arrived at the Afyonkarahisar train station they nearly ended up on a train taking deported Armenians in the opposite direction.

Luckily, one of the train station’s officials recognized them and knew of their relation to Migran Topalian – Agavni’s grandmother’s brother who held a high position in the railway company. Having spoken to Topalian on the phone, the official put them on a train going to Smyrna.

They were thus able to avoid the tragic fate that befell the rest of their relatives who stayed behind in Afyonkarahisar — all of them were killed during the Genocide.

It wasn’t until after World War I, in 1918, that Agavni was able to once again see her parents’ house in Afyonkarahisar. “There was an Armenian-American officer, captain Hems (his real name was Ambartsum), who came to estimate the damages. That was the last time she saw the house where she was born. All of their belongings were gone,” Raffi remembers.

Agavni spent the war years with her grandmother Maria and her aunt in Izmir. “My grandmother went to the Armenian Ripsimyan girls’ school, where she learned Armenian and French, which she spoke without an accent – a rarity in her generation,” says Raffi. But in September 1922 Turkish nationalists set fire to Smyrna in their quest to annihilate the city’s Armenian and Greek minorities. The massacres began anew, and 12-year-old Agavni lost her grandmother in the crowds.

Fleeing the conflagration, Agavni and her aunt tried to swim to safety on nearby boats. An Italian ship picked them up and delivered them to Piraeus in Greece. Several months later they left for France: one of Agavni’s aunts, Satenik, was living in Arnouville, north of Paris. The new exile and the accumulated losses left an indelible mark on the orphaned girl’s life.