Viro Arnold

Born in Armenia in 1969, Viro Arnold has lived and worked in Germany for 20 years. After a humble start as a street artist, his status in the art world has grown. Today, leading critics describe his technique as impressive and realistic – a special gift, which enables him to convey his model’s personality in his very own masterly fashion.

Viro himself traces that style back to the traditional Armenian school of painting. He studied art at the Panos Terlemezian Academy from 1984 to 1988 and graduated with distinction. As Armenia’s economic and political situation deteriorated in the wake of the Nagorno-Karabakh War, Viro moved to Russia in 1991 and enrolled at the Ilya Repin Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. His father was suffering from cancer and Viro believed this was his best chance of earning the money to pay the medical bills. He painted through the night and by day he displayed his work on Nevsky Prospect, not far from the Kazan Cathedral. Selling a picture from time to time kept him going until he met Tigran Sahakian, a fellow Armenian who was none other than the vice-director of the Museum of the History of Religion, formerly located in the Kazan Cathedral.

“He asked me if I wanted to exhibit my paintings there, and also invited the press. I was given the opportunity to show 20 or 30 of my works and the Vechernij Leningrad newspaper even wrote an article about it,” Viro recalled. After that Sahakian suggested exhibiting the paintings in the Museum Ettlingen in Germany, a partner of the Museum of the History of Religion.

Viro went to Germany for the first time and after a few months settled in Stuttgart. Once again, his new start was humble, painting portraits for people on the streets. One day he got his break: a job decorating a pool hall with images of sporting champions.

“I liked the job a lot because I had never done anything like it before.”

Lucky escape

It is mostly thanks to his mother, Seda Muradian, that he became a painter. Her parents both survived the Armenian Genocide. “My maternal grandfather, Mushegh Muradian, was bedridden when I knew him. He was already very old when I was born and died when I was just five. He had been born in Bitlis, probably around 1902. He was 12 when the Genocide began. He and his seven-year-old brother managed to get out of Bitlis. They took gold and other valuables, put them on donkeys and escaped under cover of darkness. Unfortunately, they lost most of what they had taken when one of the laden donkeys ran off while they were crossing a river. My mother later told me that at family reunions her uncle would ask, half joking, if my grandfather had not been able to save some of the gold after all. This was one of the few occasions when their flight from Bitlis to Yerevan was ever mentioned.”

Musheg’s father produced and repaired rifles for the Armenian self-defense units. He was in his barn when the Turks burned it down with him trapped inside. “Somebody must have betrayed him. His mother was thrown into a tonir, the traditional Armenian earth oven for baking bread, where she burned to death,” remembered Viro.

Viro’s mother, Seda Muradian, worked in the editorial office of the renowned Armenian newspaper Hayreniki Dsajn, the Voice of the Home Country. She was in contact with the best and most talented artists of the time. “They would often come by and bring paints and brushes: that really got me interested and started me on my own path.” Viro’s first painting, which was published in a children’s magazine, was done in watercolors and showed a musician playing the guitar. He was only six years old. His parents later sold the house they inherited from Viro’s grandfather to pay tuition fees for their two sons.

“I am forever in their debt,” Viro said.

His maternal grandmother, Marusya, came from Marash. She and her family had left the Ottoman Empire in time to escape the massacres. His paternal grandmother, Satenik Budaghian, came from Bitlis and was the only member of her family to survive. She was raised in an orphanage. “Unfortunately, there are no pictures left of my grandparents: they got lost when we sold our house in Yerevan and moved to Russia,” Viro lamented.

From streets to galleries

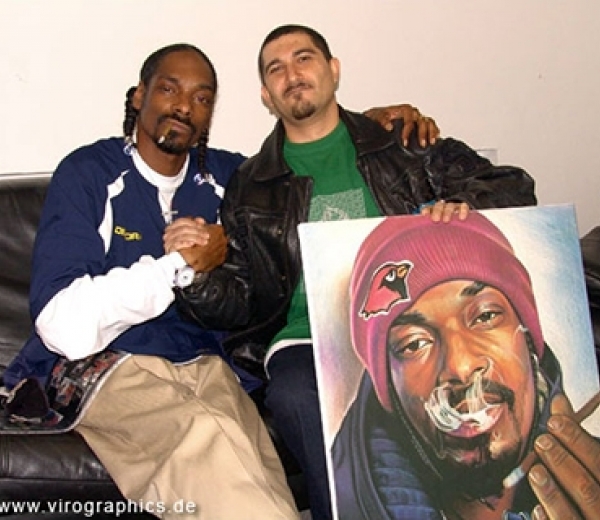

In 2000 and 2001 Viro exhibited his paintings in New York and Los Angeles. Ulli Kühnert, Creative Manager with Universal Music, commissioned him to paint portraits as gifts for the stars. In 2001 Viro exhibited his paintings at the Las Vegas Magic Show and met boxer Floyd Mayweather Jr., who was eager to sit for the artist. Viro’s works quickly became very popular with American celebrities. Soon after, Snoop Dogg and many more wanted to have their own Viro portraits.

|

Viro Arnold with Snoop Dogg. Los Angeles, 2004 |

Back in Germany, Viro’s works were soon discovered by none other than Alex Gernandt, editor-in-chief of Bravo, Germany’s most popular teen magazine. For the third time, a chance encounter gave Viro’s career a boost. For the next seven years, his portraits appeared as posters in Germany’s biggest-selling magazine, reaching an audience of more than 250,000 people each week. From Bravo, Viro moved to work with Werder Bremen, a football club in Germany’s Bundesliga, painting works that were sold as art prints.

“It has always been my dream to be invited by on to Stefan Raab’s TV show,” Viro said. “One day Arthur Abraham celebrated a win by carrying my portrait of him around the ring. Stefan saw it and joked that it might be nice if his colleagues could commission a similar portrait for him. It wasn’t long before my phone rang and I was invited onto the show. It’s the little successes that make the big one,” Viro said with conviction.

|

Viro Arnold with Stefan Raab |

Today Viro has his own studio and lives together with his wife, Hasmik Manukyan, and their seven-month-old son Ruben in Fellbach, a town at the northeastern city limits of Stuttgart. In recent years his work has expanded into new areas, but painting portraits remains his favorite creative activity.