Seda Galoyan

Submitted by global publisher on Thu, 06/23/2016 - 20:16

English

Intro:

“That’s it. The greens have come out. The Armenian children won’t die,” the caregivers at the orphanage would say whenever spring came to Turkey. They were referring to the special characteristic of Armenian cuisine, where dishes are often seasoned with lots of herbs. In 1915, hunger turned those greens into a daily meal for children at the orphanage; among them was the grandfather of Seda Galoyan.

Weight:

-8 800

Story elements:

Text:

“That’s it. The greens have come out. The Armenian children won’t die,” the caregivers at the orphanage would say whenever spring came to Turkey. They were referring to the special characteristic of Armenian cuisine, where dishes are often seasoned with lots of herbs. In 1915, hunger turned those greens into a daily meal for children at the orphanage; among them was the grandfather of Seda Galoyan.

Text:

Sitting in a large leather chair in her office, Seda Galoyan tells the story of her family. The room’s windows open out to the schoolyard, where children play. The wind carries in bits of their conversations and laughter.

“My grandfather’s name was Aram Egiazarian. His father, my great-grandfather Egiazar, had four children. He lost two of his daughters during the massacres, but he was able to smuggle his only son and his youngest daughter out of Van. Great-grandfather himself died on the road. Grandfather and his sister Almast were left on their own. They were starving and hid in the mountains, until somebody picked them up,” says Seda.

Image:

Text:

|

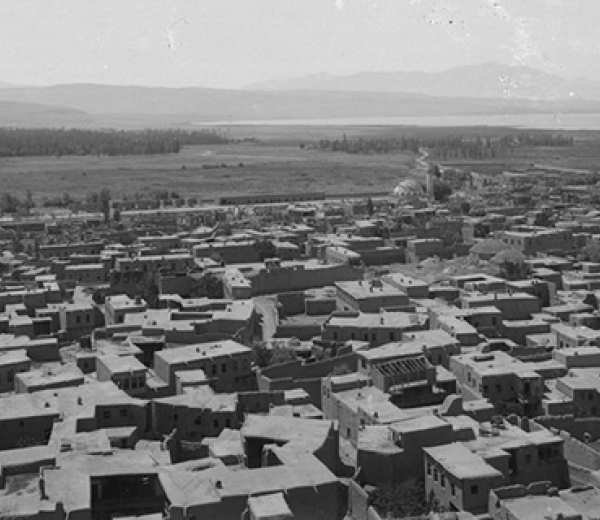

A view of the city of Van |

The haggard teenager told his saviors how he carried his young sister in his arms through the horrors of the war. He also talked a lot about his father, Egiazar Egiazarian. He was a nobleman and a well-known pedagogue. He ran his own school for children from poor Armenian families, giving everyone an opportunity to receive a good education.

Seda takes off her glasses and turns to the window: “This runs in the family. All of my ancestors were teachers. I’ve been teaching children for 50 years already. Just think of it – 50 years.” It’s not that she’s boasting, more like trying to understand: is that a lot, or not?

Seda Galoyan began her career in Yerevan as a physics teacher. Today, she is one of Moscow’s 100 best-known female residents, and has in-depth knowledge of Oriental languages. She is an “honorary teacher of the Russian Federation” and the principal of school #2042. The school was modeled after the Lazarev College of Oriental Languages, which was later given the status of an institute. Until the beginning of the 20th century, this institution was located on Armyansky Pereulok (Armenian Lane), where the Embassy of Armenia now stands. The majority of the college’s students were children from Armenian families who lived in Russia at that time.

“At our school, we also put a special emphasis on Oriental languages. Here we teach Armenian, Persian and Arabic. These are required courses, just as Russian and English languages are. I want the school to be a place where anyone can enroll their kids and be sure that they’ll keep their national and cultural identity,” Seda says.

Children feel at home here. Even on school breaks they often come by — some for drawing lessons, some for dancing. “It’s very interesting to watch the ethnic Russian kids give a virtuoso performance of Armenian dances. It’s incredible! And you should’ve seen our dark-haired Armenians wearing national Russian shirts for Maslenitsa (Carnival)!” Seda laughs. Living among the children keeps her spirit young.

Children of 38 nationalities are enrolled at the school. At the end of the school day, a great laughing crowd of Russians, Armenians, Syrians, Pakistanis, Colombians, Dagestanis and Georgians leaves the building. A new girl recently joined the school; Judith is from Africa.

“You know what I realized? We can’t accumulate our pain and grievances,” says Seda. “Several years ago, there was this episode, which I will remember for the rest of my life. I was the principal of the Armenian school in Moscow back then and there was a Turkish school not far from us. We got along well – organized academic Olympics together and held celebrations. Once they invited us to perform at a concert in honor of Children’s Day. The Turks celebrate this day on April 23. I was ill at ease; it was a difficult moment. I went to our church and I asked bishop Ezras for advice, and he said: ‘We should strive to establish good neighborly relations, so go and dance. There’s nothing bad about this.’ And you know, we went to this celebration and on that day, on the eve of our tragic date, we performed the berd dance, which means ‘fortress.’ The Turkish ambassador was in attendance. After the performance, he came to me and got down on his knees. The whole room gave us a standing ovation.” Seda falls silent for a bit, as if gathering her strength, and completes her thought: “If we only live with pain, nothing good will come out of it. We have to look to the future.”

After this event Seda was invited to Istanbul, where she visited an old Armenian school: “I was walking on marble floors and thinking of my ancestors, who had walked these cold stones more than 100 years ago,” she remembers. “There was a large mulberry tree in front of the school, and underneath it sat old Armenians playing backgammon. I am telling you this, and there’s a lump in my throat. It was a very profound shock.”

Seda could never stand conflict, even simple disputes. This fear is in her blood. In the school, there are Catholics and Protestants, Armenian Gregorians and Russian Orthodox, Shia and Sunni Muslims and even Zoroastrians.

She has tried to make sure that this little world has no boundaries separating people. “One thing I’m sure of is that my kids, my students, will never point a gun at each other, no matter what,” she says.

“My mother is a teacher. She taught Russian language. And grandmother is also a teacher. My uncle, too. And my daughter, and my son. It seems there’s something in our blood, we like to teach everyone,” Seda continues. “I haven’t told you about my grandmother! After everything that happened, grandfather Aram and his sister moved to Kislovodsk. There, grandfather met his love, Marina Eliseeva. So my grandmother is Russian, yes. They fell in love and got married very young.”

Their sons Hakop, Haik and Rafael and daughter Amest, Seda’s mother, were born in Kislovodsk. Aram continued his family’s tradition; together with his wife, he taught Armenian kids who escaped from the Ottoman Empire their native language, literature, history and math. It would seem that this was a happy ending, but fate decreed otherwise. Grandfather Aram was executed by firing squad in 1933; the family was repressed and exiled to Siberia. “My ancestors were very industrious. They earned their money and built the largest and the most beautiful house in the area. Of course, many people envied them. Plus grandmother was from a noble family.”

Seda Galoyan’s mother miraculously escaped Soviet repressions and moved to Yerevan, where she lives to this day. Her grandmother and her three sons were later exonerated and moved to Armenia as well. But there wasn’t much time for joy, as World War II began soon. The two eldest sons went missing in action. The younger son, Rafael, graduated from the teachers college and continued the family tradition, becoming a teacher of Russian language and literature.

Amest Egiazarian had a happy life. She married Vagan Galoyan, the director of the Yerevan branch of the Soviet tourist agency Intourist, and they had two daughters.

Seda Galoyan believes that the nation’s strength lies in keeping the memories of its ancestors and its ancestral lands alive. “We have such land, such mountains. I was once coming from Yerevan and we stopped in the mountains. I saw this huge rock. Right on the rock, there was an apricot tree dotted with small fruit. I was amazed — an apricot tree is growing out of the rock! How can this be? But this is what our people are. We grow everything on rocks. Our mountains, our rocks — this is us,” says Seda.

“It can be painful sometimes, but we have to hold our ground. We are made of stone.”

On her way out, Seda suddenly stops at the door: “There is one thing I want to say, the most important thing. When my kids graduate from this school, I always tell them, especially the Armenian children: be worthy of your nation! This is very important. There are no bad nations. There are people who make mistakes. And there are those who are worthy of their nation.”

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.

Subtitle:

Distinguished teacher creates a world with no boundaries

Story number:

37

Header image: