Armenian Genocide at a Glance

A brief timeline of the Armenian Genocide with key dates and facts

Background and Prelude: Late 19th century

1894-1896

July 1908

On July 23 Ottoman army officers staged a successful coup against the Bloody Sultan Abdul Hamid. Armenians welcomed his dethroning in hopes that minority rights would receive better protection under the rule of the Young Turks and their Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) (Ittihad ve Terakki), which claimed to subscribe to slogans of the French Revolution: “Liberty, equality, fraternity.” Soon after the coup the Ottoman Constitution was restored, followed by a series of parliamentary elections. On the eve of the Armenian Genocide, Armenians had nine parliamentarians and formally enjoyed better civic liberties.

April 1909

Beginning of 1910s

January 23, 1913

As a result of the coup d'état, the government fell under full control of the Committee of Union and Progress. Talaat, minister of Interior Affairs, Enver, minister of War and Djemal, minister of the Navy (known as the “Triumvirate of Three Pashas”) became the de facto rulers of the Ottoman Empire.

February 8, 1914

November 2, 1914

The Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers (the German Empire, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria) against the Allies (the Triple Entente of the United Kingdom, France and the Russian Empire, gradually joined by Italy, Japan, United States, Romania, Greece and others).

The Genocide: January 1915

The Turkish army was completely defeated by Russians in the Sarikamish area (now in northeastern Turkey), losing 70,000 men. Arriving in Constantinople on January 21, Enver Pasha made a speech congratulating Armenians for fulfilling their duties on the Caucasian Front and elsewhere. Meanwhile, speaking to the publisher of the “Tanin” newspaper and the deputy speaker of the Ottoman Parliament, Enver Pasha announced that the defeat resulted from Armenian treason and that it is time for Armenians to be deported from the eastern provinces en masse.

February 1915

To implement the deportations and massacres efficiently the CUP Central Committee formed the “Executive Committee of Three,” comprised of Doctor Nazim, one of the founders of the "Committee of Ottoman Union" secret society in 1889 which later became the CUP, Behaeddin Shakir, a founding member and leader of CUP, the main transformer of the "Committee of Ottoman Union" into a political organization and later an official political party, and Midhat Shyukri, the CUP General Secretary. This committee was tasked with setting the timelines for deportations by provinces, the destinations to which Armenians were to be sent as well as the concentration camps for the ultimate annihilation of the deportees.

The “Special Organization” (“Teşkilat-i Mahsusa”) earlier formed from convicted criminals was put at the committee’s disposal and was subsequently frequently used as muscle power in the slaughtering of the Armenian population. For this very purpose thousands of robbers, bandits and murderers were freed from Ottoman prisons.

February 18, 1915

Behaeddin Shakir, the plenipotentiary of the UPP’s Central Committee, sent letters to the party’s regional delegates informing them of the plan to exterminate Armenians.

February 1915

By decree of the War Minister Enver, tens of thousands Armenian soldiers in the Ottoman army were disarmed and assigned to labor detachments. Soon after they were divided into groups of 50 to 100 and killed.

March 1915

Armenian officials throughout the empire started getting dismissed while arms were confiscated from the Armenian population (allowed by law since 1908).

Early April, 1915

Mass deportations of Armenians began in Zeitun (now Süleymanlı, in southern Turkey) and Dyortyol, as well as Aleksandret (now Iskenderun, in southern Turkey) and Adana– all in southern parts of Anatolia very far from the Caucasian front line. The leaders of the Armenian community of Sivas were arrested. The inhabitants of Armenian villages of Sivas, Bitlis and Erzerum vilayets were persecuted and their possessions pillaged.

Massacres began in the Armenian villages of Van vilayet. Armenians of the city of Van disobeyed the governor’s order to lay down arms. The city was besieged by the Ottoman army and Kurdish irregular regiments, who met with fierce resistance on behalf of the Armenians. In May the advance battalions of the Russian troops and the Armenian volunteer detachments finally reached the city and lifted the Turkish siege, forcing the Ottoman soldiers to flee.

April 24, 1915

Two hundred and fifty Armenian intellectuals and community leaders were arrested in Constantinople. They were sent to Chankri and Ayash, two concentration camps close to Ankara. Most of them perished on the road to exile to the southeast of the empire. The wave of arrests and deportations of Armenian intellectuals and community leaders soon rolled across the country. These events are symbolically considered the official start of the Armenian Genocide, which lasted until 1922-1923.

Early May, 1915

The Interior Minister Talaat asked the cabinet to legalize the Armenian deportations due to what he called "Armenian riots and disorders, which had arisen in a number of places in the country."

May 9, 1915

The government of the Ottoman Empire made a decision to deport all Armenians from Eastern Anatolia (mainly from the six vilayets with the largest Armenian populations) to the deserts of Mesopotamia in the south.

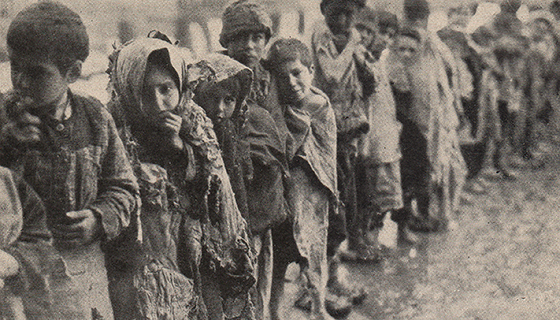

The male population was brutally executed while women, children and elderly were taken to death caravans, accompanied by gendarmes. The deportations soon turned into an outright offensive on the Armenian population complete with killings, pillaging and rape. The majority of the deportees were killed or died on their way from torture, illness, thirst and hunger – on average only ten percent reached the deserts in Mesopotamia, where the chance to survive was also next to none.

May 22-25, 1915

During a meeting between the Young Turks and the Special Organization at the Nur Osmanie Center in Istanbul, Talaat extensively presented the ways and procedures for deporting Armenians, taking control of their property and resettling Armenian villages.

May 24, 1915

France, Russia and Great Britain (the Allies) issued a joint statement labeling acts of violence against the Armenian people a crime against humanity and civilization. The Allied governments publicly announced that they would hold all members of the Ottoman government and their agents implicated in the massacres personally responsible.

May 27, 1915

The UPP’s Central Committee passed the “Temporary Law of Deportation” (Tehcir Law), permitting the Ottoman government to deport anyone “perceived” as a threat to national security.

June 21, 1915

Talaat ordered the deportation of “all Armenians with no exception” residing in the nine eastern vilayets of the Ottoman Empire with a small exception of those who were deemed “useful” for the Ottoman state.

July 5, 1915

The deportation area was widened to include the Empire’s western provinces, such as Ankara and Eskishehir, as well as the Euphrates Valley.

July 13, 1915

Talaat announced that deportations were implemented for the sake of the “ultimate resolution of the ‘Armenian Question’.”

September 13, 1915

The Ottoman parliament passed the "Temporary Law of Expropriation and Confiscation," stating that all property, including land, livestock and houses belonging to deported Armenians was to be confiscated by the authorities. On September 15 “The Law on Abandoned Goods” was ratified by the Turkish Senate.

Throughout 1915

Despite the Ottoman efforts to hide the ultimate goal and scale of their undertaking, many eyewitnesses, including foreign diplomats, missionaries and relief workers regularly spread word of the atrocities. In August 1915 the Ottoman authorities forbade killings of Armenians in areas where American consuls might see them. In January 1916 it was forbidden to take photos of Armenian corpses.

Throughout 1915 and beyond

The Armenian Genocide received broad coverage in international media of the time. The New York Times alone covered the Armenian massacres in some 145 articles in 1915 with headlines like “Appeal to Turkey to Stop Massacres.” In an era when the term “Genocide” was yet to be invented The Times described the actions against the Armenians as “systematic,” “authorized” and “organized by the government.”

1916

Western Armenia was almost fully cleared of its Armenian population. Russian troops entered deep into the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire. In the city of Erzerum (which was referred to in the Russian media as the “capital of Turkish Armenia”) and in the entire province only a handful of captive Armenian women and minors were found alive. From the whole Armenian population of Trapezund (Trabzon in northern Turkey) only a handful of orphans and women survived with the help of Greek families.

1917

Due to the February Revolution in Russia, the Russian soldiers deserted the area. The situation on the Caucasian front changed in favor of the Ottomans, allowing the Young Turks to continue annihilating the Armenian population.

Early 1918

The Ottoman troops captured Erzincan and Erzerum. The Genocide survivors who had returned to their homes after the Russian advances once again faced the threat of violence.

March 3, 1918

By signing the Brest-Litovsk Treaty with the Central Powers (Germany, Turkey, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria) Russia obliged to withdraw its forces not only from Ottoman territories, but also from the Kars, Ardahan and Batum regions, which were under Russian control at the start of the war. This gave the Young Turks an opportunity to pursue their genocidal agenda in Eastern Armenia as well. Soon after this the Ottoman forces captured Sarighamish, Kars, and on May 15, Alexandropol (present-day Gyumri), brutally killing all Armenians on their way.

Late May

Only by being victorious in the Sardarapat and Bash-Aparan battles did the Armenians succeed in safeguarding the population of Ejmiatsin, Yerevan and the vicinities, including hundreds of thousands of refugees from Western Armenia.

October 30, 1918

The Ottoman army capitulated by signing the armistice of Mudros with the Allied powers. In the Caucasus, the Ottomans had to retreat to the pre-war borders between the Ottoman and the Russian Empires.

February 1, 1919

A court-martial to be established to address war crimes is convened in Constantinople by the new Ottoman government on the Allies’ orders. The verdict issued by the court recognized the Armenian massacres and condemned four out of the 31 perpetrators on trial – Talaat, Enver, Jemal and Nazim (“in absentia” as they have managed to flee the country) – to death for crimes against humanity, while the remaining 27 were sentenced to imprisonment for different lengths of time.

1920

Kemal Ataturk, the new ruler of Turkey, terminated the operation of the court martial. Governors executed by the court’s verdict were recognized as martyrs and heroes of the Turkish nation. Some of those found to be war criminals led politically influential lives in the nascent Turkish state.

September-October, 1920

Without a declaration of war, the Turkish army repeated the Ottoman army’s offensive in Eastern Armenia by capturing the Kars province and occupying almost half of the Republic of Armenia, including Alexandropol. Around 30 villages in the Alexandropol and Akhalkalak regions were overrun and their inhabitants slaughtered.

October 20, 1921

The Turkish-French treaty was signed in Ankara, resulting in French troops pulling out of Cilicia from December of 1921 to January 4, 1922. The renewed threat of massacres led 160,000 Armenians of Cilicia to migrate to Syria, Lebanon and Greece.

August 10, 1920

In the Paris suburb of Sevres the victorious states of World War I signed a treaty with Turkey. Articles 88 and 89 of the Treaty recognized the Republic of Armenia as a free and independent state. The Articles state: “Turkey and Armenia, as well as the higher powers, agree on leaving the border determination of Erzerum, Van and Bitlis between Turkey and Armenia to the decision of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and accept his decision, as well as all the means he can suggest for Armenia to have sea access and on the mentioned territory any demilitarization of the Ottoman territory… From the moment of adopting this resolution Turkey waives all rights to these territories.”

September 9, 1922

The Turkish army entered Izmir and massacred 10,000 Armenians and 100,000 Greeks. Four days later the Armenian and Greek quarters of Izmir were set afire. Turkish troops cordoned off the shore to entrap Armenians and Greeks in the fire zone and prevent them from fleeing.

The Aftermath: July 24, 1923

The Treaty of Lausanne was signed between Turkey and Allied Great Britain, France, Italy, Greece, Japan and Romania. The delegation of the Armenian Republic was not allowed to take part in the conference as it no longer represented Armenia, which had been absorbed into the Soviet Union.

The Lausanne Conference also broached the “Armenian Question,” but the Turkish delegation spoke out against the idea of founding any Armenian state on the territory of Turkey. In the end, the treaty included no mention of Armenia or Armenians. Thus the Lausanne Conference temporarily closed the “Armenian Question” and territories that were to be given over to Armenia by the Treaty of Sevres were incorporated in the ethnically cleansed, newly formed borders of the Republic of Turkey.

September 1939

On the eve of invading Poland, Adolf Hitler declared: "Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?"

1943

Against the backdrop of World War II and Nazi atrocities against the Jews famous Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term “Genocide.” The term was further expanded upon under the United Nations convention of 1948 on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Lemkin mentioned in an interview that the word, which combines Greek and Latin roots, was informed by the Armenian experience and retrospectively referred to the Armenian massacres by Turks as “Genocide.”

Based on materials of the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute.

To learn more about the chronology, as well as testimony, eyewitness accounts, memoirs of survivors, archival documents, press coverage, photos, bibliography and other materials related to the Armenian Genocide please visit the following resources:

Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute

Original video of Raphael Lemkin’s remarks on Armenian Genocide