Syrian Armenians: Unsung Heroes Who Saved Lives

Submitted by global publisher on Tue, 06/09/2015 - 19:34

English

By Khatchig Mouradian

The city of Aleppo constituted a major hub for deportation routes during the Armenian Genocide. Convoys that survived the treacherous journey began to reach the area in May 1915. In a report dated June 5, the U.S. Consul in Aleppo Jesse Jackson explained: “There is a living stream of Armenians pouring into Aleppo from the surrounding towns and villages…No animals are provided by the government, and those who are not fortunate enough to have means of transport are forced to make the journey on foot.”

Many had no shelter. In a memoir he wrote decades later, John Minassian, a deportee from Sivas, revealed that he found refuge for a short time in the courtyard of Reverend Hovhannes Eskijian’s house in Aleppo, where “some 20 families had been crowded… all were in tatters and were slowly dying of hunger and lack of care. Barely alive, they had little protection here, but they did have a friend in the Reverend.” According to eyewitness Hayg Toroyan, “The Armenians of Aleppo generally accepted the deportees with open arms. They opened their homes to them…. Yet the streets, the fields, and forgotten corners of the city were full of thousands of desolate people whose nests had been destroyed.”

The 10,000-strong Armenian community in Aleppo mobilized to assist the deportees. The Armenian Apostolic Church in Aleppo initially took ad hoc measures to support the new arrivals. On May 24, the church launched a much more coordinated effort, inviting a group of community leaders to form the Council for Deportees (henceforth, the Council) tasked with “caring for the immediate financial, moral and health needs” of the arriving Armenians.

The city’s Armenian Evangelical and Catholic churches launched their own relief initiatives and coordinated efforts as needed. U.S. consul Jackson noticed this groundswell of support from the community early on and reported to his superiors on June 5 that the deportees are being “taken care of locally by the sympathizing Armenian population of this city.” In another report, he noted: “Each religious community has a relief committee to care for its own.”

The Council immediately prepared lists of the deportees in Aleppo and neighboring towns and villages, to ascertain their housing, food and medical needs. From the onset, the Council did not confine its efforts to the city or even the province of Aleppo, sending aid and dispatching missions all the way to Der Zor. As the Armenian Apostolic Church did not have a presence there, Der Zor’s Armenian Catholic Prelacy served as a local partner, and communication between the two was achieved via telegrams sent from the Armenian Catholic Prelacy in Aleppo to its counterpart in Der Zor. The Catholicos of Cilicia Sahag II Khabayan, who had arrived in Aleppo from Adana on May 28, played a key role in these relief efforts.

The Aleppo Armenian community even attempted to change the government’s deportation policy in May and June of 1915. It first appealed to the Ottoman Minister of the Navy and the Commander of the Fourth Army, Cemal Pasha, to spare the Armenian deportees who had found refuge in the city from being re-deported to the desert. Not receiving a response, the community leadership appealed this time to the Prime Ministry, the War Ministry and the Interior Ministry, begging them to stop these orders. When no word came from the capital either, the Council sent yet another appeal, signed by deportee women, to the Sultan himself. The deportations continued, however.

The Catholicos quickly realized that appeals to Ottoman Turkish authorities accomplish little. In a letter on July 19 to the Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul, Zaven Der Yeghiayan, he wrote: “The [Armenian] people has lost its mind; it doesn’t understand the enormity and nature of the pain…. They push me to appeal to the Sultan and the elite. They push me to telegram and ask for bread for the hungry, but I know that every appeal, every single act of begging is useless and only opens the door to stricter measures and more evil.”

The government soon cracked down on the relief efforts of the Aleppo Armenian community, imprisoning certain leaders, exiling others, including members of the clergy, and even the Catholicos, who was sent to Jerusalem. In the months that followed, tens of thousands of deportees would die in concentration camps in Ottoman Syria, particularly along the Euphrates River and in Ras ul-Ain. In the summer of 1916, up to 200,000 survivors would be massacred in Der Zor.

Still, the humanitarian network in Aleppo was successful in anchoring thousands of Armenian deportees in the city. Various strategies were used, most notably employing deportees without pay in factories and hospitals that serviced the military and securing permission from local authorities to open and expand orphanages that sheltered thousands of Armenian children. This network, the core of which constituted religious and civic leaders of the Armenian community, was buttressed by missionaries and other foreign nationals living in the area and sometimes supported by western diplomats.

Until the end of World War I, and even in the years that followed, the relief network continued to support the thousands of deportees who had managed, one way or another, to disappear into the fabric of the metropolis or seek refuge in orphanages and community centers, escaping re-deportation to the desert. Thanks, in large part, to the efforts of the Aleppo Armenian community, thousands of Armenians survived the genocide and rebuilt their lives in the diaspora.

Khatchig Mouradian is the Coordinator of the Armenian Genocide Program at the Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights at Rutgers University, where he also teaches in the history and sociology departments.

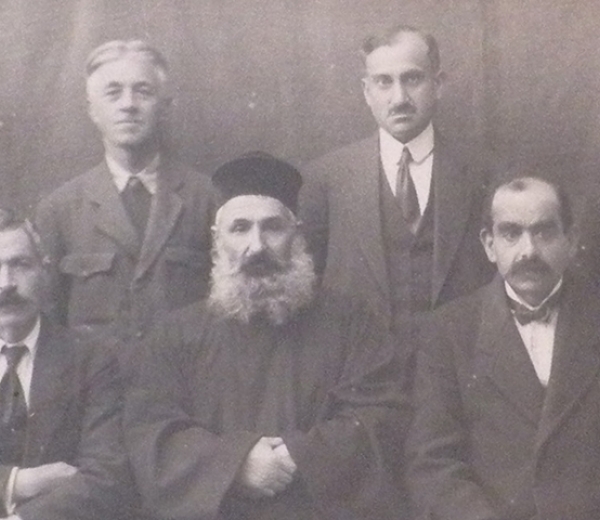

Photo: Father Haroutyoun Yessayan (center), who chaired the Council until Ottoman Turkish authorities arrested and imprisoned him. (Source: AGBU Nubar Library, Paris)

Image:

Display type:

Big

Weight:

-15