One can still find this oasis of low-rise, white-walled houses in the very center of Singapore, amid skyscrapers and extravagant buildings made of metal and glass. High arcades that connect the houses create a labyrinth made up of enclosed patios, where palm trees provide the guests with shade.

To this day, the historical hotel’s main entrance is located on Beach Road. This busy motorway used to be a quiet street running along the seashore. The shore was moved several hundred yards into the sea a long time ago, as Singapore continues battling for land with surrounding waters. Land plots that were wrestled away from the sea have been used to create a new Botanical garden, museums and walkways.

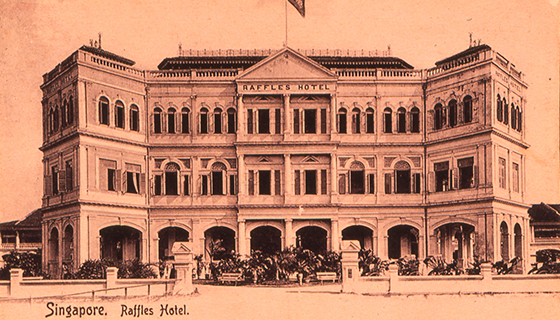

But Raffles Hotel perseveres in its original location, though it is no longer just a hotel. At the end of the 19th century it became famous for its excellent service and hospitality, and today it stands as a testament and an eyewitness to Singapore’s almost two-century-long history.

It brings together memories of colonial English prejudices and the shrewdness of Armenian businessmen, the affinity that the first well-off European tourists had for exotic travel and the special atmosphere so welcomed by English writers and poets. It was at the hotel’s Long Bar — the principal meeting spot for 19th and 20th century expats — that bartender Ngiam Tong Boon invented the Singapore Sling cocktail, which, along with the Raffles Hotel itself, have long become part of Singapore’s national heritage.

Somerset Maugham, who often stayed at the hotel for long stretches of time, likely tasted the cocktail, though its original recipe was lost. Maugham once wrote that “Raffles stands for all the fables of the exotic East!” The hotel became a refuge where the writer could go to work on his prose, and his words served as an excellent advertisement that attracted new guests.

Brothers Sarkies