Vahagn Hayrapetyan

“During the deportations, a Turk from one of the villages took me and cared for me for a few months. I was an energetic and handsome child. The Turk treated me well. News had gotten out that there was an Armenian child in the village, and they took me in the second wave of deportations,” says Vahagn remembers his grandfather saying.

| Bedros (center) seated in front of a shoemaker’s table with fellow workers, Istanbul, 1924 |

| Bedros Hayrapetyan and a friend with their photo equipment |

| Bedros Hayrapetyan and Hripsimeh Vardanyan on their wedding day, Alfortville, France, 1933 |

| Bedros (center) wearing a butcher’s apron, France, 1932 |

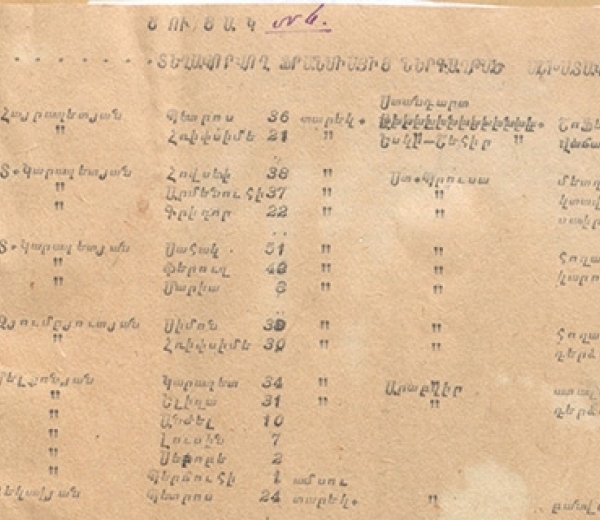

| A list of repatriates from France to Soviet Armenia. The names of Bedros (36) and Hripsimeh (21) Hayrapetyan appear at the top. Image courtesy of the National Archive of Armenia. |

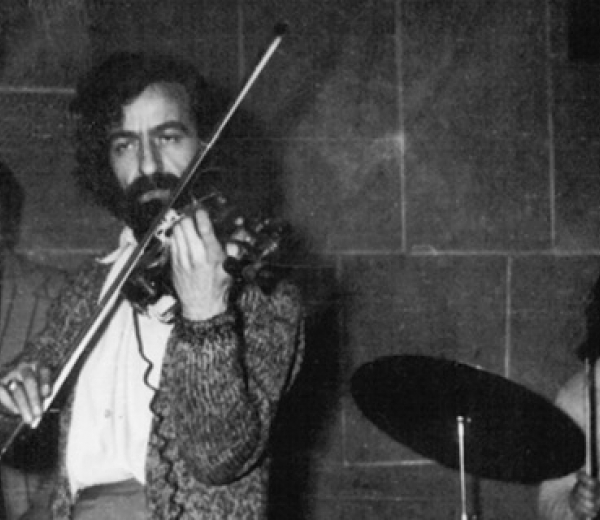

The couple’s first child, named Garabed after Bedros’ father, was born in 1942. “My grandmother would say that she once saw a movie in France about a violinist. She was so taken with the main character that she decided that her child would become a violinist as well,” recounts Vahagn. Thus a film decided the fate of their son Garo Hayrapetyan, a famous violinist.

| Violinist Garo Hayrapetyan |

Bedros’s heirs – two children, five grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren – grew up in Yerevan and established a musical dynasty. Bedros’ grandsons Vahagn Hayrapetyan and Levon Pouchinyan became a pianist and a trumpeter, respectively. Bedros’s great-grandson, pianist Armen Pouchinyan, is already a medal winner at the age of 11.

| Garo and Vahagn Hayrapetyan |

Vahagn cherishes the memory of his grandmother Hripsimeh’s “manti.” “Manti was the dish we liked best of all. Those small patties…No one’s, however they make them, are ever as tasty as hers. There were manti days when the whole family would get together,” Vahagn recalls. “And my grandfather really knew his meat. Even with his eyes closed, he could skin a lamb so skillfully so as not to damage anything. And what basturma he’d make! It melted in your mouth. I’ve never eaten such delicious and authentic basturma.”