Vartkess Knadjian

|

The Knadjians at a baptism in Addis Ababa in 1924. |

In 1896 Ethiopian Emperor's Menelik II troops defeated the Italian colonial army in the Battle of Adwa. To maintain the victory and modernize the country, the emperor entrusted most of the state business to Armenian middlemen, whom he encouraged to settle down in his country. The first wave of persecutions of Armenians soon swept over the Ottoman Empire, leading several thousands of Armenians to heed the emperor’s call and move to Addis Ababa.

|

Vartkess’s grandmother Meroum Avakian (sitting, center) travelled from Djibouti to the Ethiopian Highlands in 1912 to get married. The Knadjian family, her future groom Nazareth (sitting, second from right), among them, welcomed her. |

As time went by, many of these emigrants arranged for families to join them or sent for a bride from their hometowns. This is how Vartkess’s grandfather Nazareth Knadjian, a carpenter from Aintab (present-day Gaziantep) in Southeastern Anatolia, came to the Ethiopian capital. Although he had just been accompanying his sister, who was going to marry an Armenian man, he spontaneously decided to stay in the country. He eventually opened Nazareth’s Café, which became a meeting point for those affiliated with the Ramkavar Party. One of Nazareth’s brothers soon followed, intending to marry Meroum Avakian from Aintab. But because he died while his bride was on her way to meet him, she eventually married Nazareth instead.

|

Antranig Knadjian created this masterpiece in 1940 for his final examination at Ecole d'horlogerie. The clock is dedicated to his father Nazareth. |

But instead of his father, it was Antranig who left for Madagascar so that Nazareth could secretly return to Addis Ababa.

|

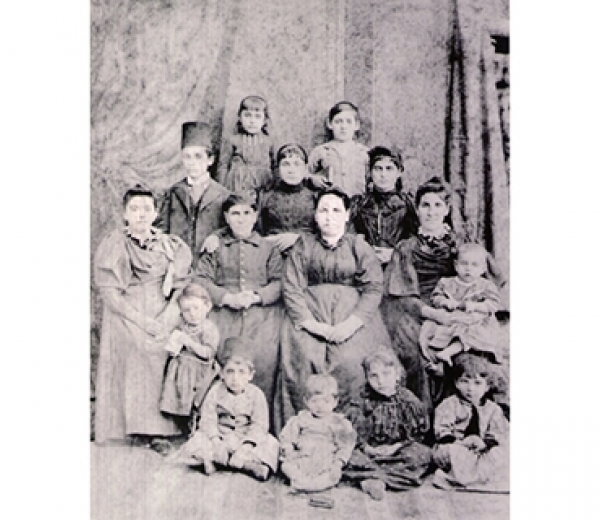

A group image without men, 1897: From the Amiralian family living in Marash, mostly women and children survived the pogroms of 1895. Osanna, Frieda Knadjian’s mother, front center. |

The imperial watchmaker

|

Frieda Knadjian with her parents Artin and Osanna Helvadjian in Palestine in 1946 |

At the end of 1947 the Arab-Israeli war broke out, and the family fled to Beirut by car. The only things they brought were some personal items and Persian rugs, which saved their lives when the car was shot at. In Beirut, Frieda became a kindergarten teacher, but quit her job when she married to Antranig and moved to Ethiopia.

|

Vartkess Knadjian’s baptism at the Armenian church in Addis Ababa |

|

Antranig Knadjian with Haile Selassie in 1955 |

Vartkess’s ties to Ethiopia, however, proved valuable one last time. The grandson of a former British ambassador introduced Vartkess to a diamond trader who owned Backes & Strauss, the world’s oldest diamond company founded in the German city of Hanau in 1789. “The diamond trade is governed by its own set of rules, its members trust each other because it’s not uncommon for their fathers and grandfathers to have done business together,” Vartkess says.

|

Vartkess Knadjian discusses the diamond factory in Armenia with former Armenian Prime Minister Tigran Sargsyan and President Serzh Sargsyan |

Vartkess joined Backes & Strauss as a trainee in 1976 and became its CEO in 2000. Three years later, he lead a management buy-out. Today, it mainly manufactures high-end watches studded with diamonds, which Haile Selassie would have loved. The company has headquarters in Geneva and London, while Vartkess continues practicing the profession in which his father was once trained. Having co-founded the Armenian Jewellers Association (AJA), he helps to build up the diamond business in Yerevan. As an Armenian, he is conscious of history and attaches crucial importance to both continuity and his company’s image. In this case, history itself is immensely valuable.